Jackie: Spring is a little late coming to the Midwest this year. But we can remember sunny days with violets and trillium blooming and rainy days that turn the grass green (instead of the snow we continue to get in mid-April). Rainy days make us think of ducks and we are going to beckon reluctant spring with stories of ducks.

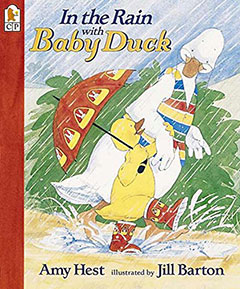

I want to start with an old favorite In the Rain with Baby Duck by Amy Hest, with illustrations by Jill Barton. This is one of those books I wish I had written. The story sets up the problem immediately. Baby Duck has to go out in the rain. She hates the rain. But at the end of the walk are pancakes — and Grandpa. Baby Duck loves both pancakes and Grandpa as much as she hates the rain.

I want to start with an old favorite In the Rain with Baby Duck by Amy Hest, with illustrations by Jill Barton. This is one of those books I wish I had written. The story sets up the problem immediately. Baby Duck has to go out in the rain. She hates the rain. But at the end of the walk are pancakes — and Grandpa. Baby Duck loves both pancakes and Grandpa as much as she hates the rain.

And the language is so much fun! First there’s the sound of rain, “Pit pat. Pit-a-pat. Pit-a-pit-a-pat.” And then there are the verbs: Mama Duck and Papa Duck love the rain. They waddled, and shimmied, and hopped. Baby Duck hates the rain that brings wet feet, wet face, mud. She dawdled and dallied and pouted.

Leave it to Grandpa to solve the problem with a trip to the attic. Once she’s equipped Baby Duck and Grandpa go out in the rain. And Baby Duck and Grandpa waddled and shimmied, and hopped in all the puddles.

I need new boots.

Phyllis: Jackie, if Amy hadn’t written this book, and if you hadn’t written it either, I would have wanted to have written it. I, too, love this book for its language, its wonderful rhythms and verbs, and its understanding Grandpa who remembers what Mama Duck has forgotten, that she, too, once didn’t like rain. And of course, I love pancake Sunday. My red rubber boots are still going strong, and once the rain comes down (rain, not snow), I plan to go splash in some puddles.

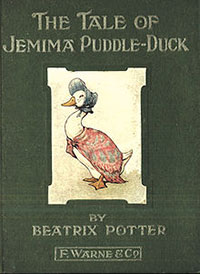

Jackie: Beatrix Potter can help us summon spring. Jemima Puddle-duck wants to hatch her own eggs, instead of letting one of the farm hens sit on them. “I will sit on them all by myself,” she says. And she leaves the farm to make a nest in the wood. “Jemima Puddle-duck was not much in the habit of flying,” but she manages to get up over the treetops and flies to an open place in the woods. She encounters an “elegant, well-dressed gentleman” with two black ears and a long full tail. We are told “Jemima Puddle-duck was a simpleton.” And we see that in action as she agrees that the gentleman has a wonderful spot for a nest in a woodshed full of feathers. Nor does Jemima suspect anything after the eggs are laid, when the “gentleman” suggests they share a meal. He asks Jemima to provide from the farm two onions and various herbs. While gathering these supplies she runs into the farm dog Kep, who is not a simpleton. And Jemima is saved from her impending doom by Kep and two foxhound puppies. Unfortunately the puppies eat the eggs before Kep can stop them. Jemima goes back to the farm and eventually hatches four ducklings. I love this story. There’s such fun in knowing more than the characters in the story. And we can sympathize with Jemima’s wish to do it herself, even if she’s not quite up to it on her own. Perhaps the best part of the story for me is Kep, whose nature seems to be to watch over the simpletons. We need more of Keps in our world.

Jackie: Beatrix Potter can help us summon spring. Jemima Puddle-duck wants to hatch her own eggs, instead of letting one of the farm hens sit on them. “I will sit on them all by myself,” she says. And she leaves the farm to make a nest in the wood. “Jemima Puddle-duck was not much in the habit of flying,” but she manages to get up over the treetops and flies to an open place in the woods. She encounters an “elegant, well-dressed gentleman” with two black ears and a long full tail. We are told “Jemima Puddle-duck was a simpleton.” And we see that in action as she agrees that the gentleman has a wonderful spot for a nest in a woodshed full of feathers. Nor does Jemima suspect anything after the eggs are laid, when the “gentleman” suggests they share a meal. He asks Jemima to provide from the farm two onions and various herbs. While gathering these supplies she runs into the farm dog Kep, who is not a simpleton. And Jemima is saved from her impending doom by Kep and two foxhound puppies. Unfortunately the puppies eat the eggs before Kep can stop them. Jemima goes back to the farm and eventually hatches four ducklings. I love this story. There’s such fun in knowing more than the characters in the story. And we can sympathize with Jemima’s wish to do it herself, even if she’s not quite up to it on her own. Perhaps the best part of the story for me is Kep, whose nature seems to be to watch over the simpletons. We need more of Keps in our world.

Phyllis: Along with the accurate and beautiful watercolors, Beatrix Potter’s wonderful language evokes the countryside of her time so vividly: the two broken buckets on top of each other for the “gentleman’s” chimney, the “tumbledown shed make of old soap boxes.” I sympathize with Jemima, who wants to hatch her eggs herself and who, although we are told she is a simpleton, seems guilty mainly of ignorance and innocent trust. Our family once fostered a duckling for a month that had hatched later than its fellow egglings, and it was indeed a sweet and trusting duckling who followed us everywhere, peeping wildly if left alone. Potter is also unsentimental in her assessment of farm life: when Jemima finally does get to sit her own eggs, we learn that she is not really much of a sitter after all, but she looks content with her own four ducklings, hatched by herself in the safety of the farmyard, under the protection of Kep.

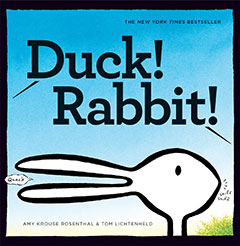

Jackie: Last April we celebrated the work of Amy Krouse Rosenthal, who had recently died. We want to honor her again with a look at Duck, Rabbit. This book is such a fun exercise in perspective, thanks to illustrator Tom Lichtenheld. “Hey, look! A duck!” And we see long bill, slightly open, oval head and eye.

Jackie: Last April we celebrated the work of Amy Krouse Rosenthal, who had recently died. We want to honor her again with a look at Duck, Rabbit. This book is such a fun exercise in perspective, thanks to illustrator Tom Lichtenheld. “Hey, look! A duck!” And we see long bill, slightly open, oval head and eye.

“That’s not a duck./ That’s a rabbit.” And what had been the duck bill becomes the rabbit’s ears, the rabbit is looking in the opposite direction. Turn the page and the illustration is the same, but the conversation continues. “Are you kidding me?/It’s totally a duck.”

“It’s for sure a rabbit.”

The two continue. Is the animal cooling its long ears or getting a drink in the pond? Is it flying or hopping? Then the argument causes the creature to leave. And the two reverse (what could be more fun?) “You know, maybe you were right./Maybe it was a rabbit.”

“Thing is, now I’m actually/thinking it was a duck.”

This story is so much fun. I can imagine that it would spark many discussions and experiments about objects or creatures that could be easily taken for other objects or creatures.

Phyllis: The book itself is its own exercise in tricks of perception and point of view: it’s all in how you interpret what you see and where you see it from. And the book ends with a wonderful twist: each voice having conceded that perhaps the other is right after all, one says,

“Well, anyway…now what do you want to do?”

“I don’t know. What do you want to do?”

“Hey, look! An anteater!”

“Thant’s not an anteater. That’s a brachiosaurus!”

This bold and clever book makes me smile. All winter I’ve been watching the city bunnies in my back yard (who have eaten my raspberry canes down to the top of the snow). Now maybe I’ll look out and find they have turned into ducks.

Jackie: There are so many duck stories. Of course, Robert McCloskey’s Make Way for Ducklings is the classic.

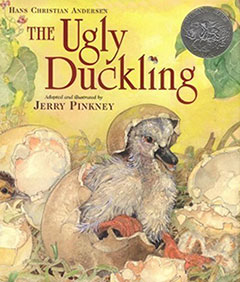

And if it’s not a classic already, Jerry Pinkney’s The Ugly Duckling soon will be. His interpretation of the Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale takes us so close to the Mama duck’s nest and the new ducklings, it’s as if we are standing in the barnyard. We know the story — the biggest duckling is so ugly that eventually even his brothers and sisters chase him and taunt him. He leaves, only to encounter hunters, and dogs with huge mouths. Eventually he finds temporary shelter in the broken-down cabin of an old woman who has a cat and a hen. The animals can’t understand another who neither lays eggs or purrs but they don’t chase after him. After three weeks the duckling leaves to find water to swim in. When icy winter freezes him into the ice he is rescued by a kind man who takes him home to his warm cabin and children. The children want to play, but the duckling, having seen mostly taunts and cruelty, does not recognize play and runs away. Pinkney does not dwell on the rest of the winter, except to say it was miserable. Relief comes in the spring when the “duckling” finds a home with his own kind, the swans. There are many versions of this story but this is my favorite. Pinkney takes the story so seriously. His ducks are real ducks and he wants us to notice them and the cat and the hen. He grabs our attention with his own attention to the details of these creatures’ lives. He makes them real while also imbuing them with the human characteristics of judgment, cruelty, curiosity, and even kindness.

And if it’s not a classic already, Jerry Pinkney’s The Ugly Duckling soon will be. His interpretation of the Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale takes us so close to the Mama duck’s nest and the new ducklings, it’s as if we are standing in the barnyard. We know the story — the biggest duckling is so ugly that eventually even his brothers and sisters chase him and taunt him. He leaves, only to encounter hunters, and dogs with huge mouths. Eventually he finds temporary shelter in the broken-down cabin of an old woman who has a cat and a hen. The animals can’t understand another who neither lays eggs or purrs but they don’t chase after him. After three weeks the duckling leaves to find water to swim in. When icy winter freezes him into the ice he is rescued by a kind man who takes him home to his warm cabin and children. The children want to play, but the duckling, having seen mostly taunts and cruelty, does not recognize play and runs away. Pinkney does not dwell on the rest of the winter, except to say it was miserable. Relief comes in the spring when the “duckling” finds a home with his own kind, the swans. There are many versions of this story but this is my favorite. Pinkney takes the story so seriously. His ducks are real ducks and he wants us to notice them and the cat and the hen. He grabs our attention with his own attention to the details of these creatures’ lives. He makes them real while also imbuing them with the human characteristics of judgment, cruelty, curiosity, and even kindness.

Phyllis: And who doesn’t want to find fellow creatures and be recognized just for being their own self?

The ugly duckling’s mother loves him so much she gives up her bath to sit on his egg after her other eggs have hatched, and she fiercely tries to protect him from the other barnyard animals. But even a mother’s love can’t always conquer prejudice and neither is the world kind. Our hearts hurt for the “duckling’s” sufferings and are immensely satisfied when he finds his own place in the world.

A few other duck books among a flock of them, Duck by author and illustrator Randy Cecil, about a carousel duck who longs to fly and who ends up fostering a little lost duckling. Duck realizes it’s up to him to teach the little duckling how to fly, but his lessons are only partly successful, so she straps Duckling to her back with her scarf and walks off to find the ones “who could teach Duckling what she could not.” When they do find a flock of ducks, the ducks take off, and the little duckling flies up to join them. But Duck, still strapped to Duckling, weighs Duckling down and realizes she must literally let duckling go. She frees herself from the scarf, duckling goes up, duck does down down down. The ducks fly away, a scarfless duck limps home, and the long winter commences, with so much snow duck that almost disappears in the drifts. Come spring, a grown-up duck wearing a scarf returns with his flock and takes duck on his back.

A few other duck books among a flock of them, Duck by author and illustrator Randy Cecil, about a carousel duck who longs to fly and who ends up fostering a little lost duckling. Duck realizes it’s up to him to teach the little duckling how to fly, but his lessons are only partly successful, so she straps Duckling to her back with her scarf and walks off to find the ones “who could teach Duckling what she could not.” When they do find a flock of ducks, the ducks take off, and the little duckling flies up to join them. But Duck, still strapped to Duckling, weighs Duckling down and realizes she must literally let duckling go. She frees herself from the scarf, duckling goes up, duck does down down down. The ducks fly away, a scarfless duck limps home, and the long winter commences, with so much snow duck that almost disappears in the drifts. Come spring, a grown-up duck wearing a scarf returns with his flock and takes duck on his back.

The book ends with the immensely satisfying last line: “And finally Duck knew what it was to fly.”

Cold Little Duck Duck Duck by Lisa Westberg Peters, with illustrations by Sam Williams, tells a rhythmic and rhyming story of a duck who comes a little too early in a miserable and frozen spring, and her feet freeze to the ice. She warms herself with thoughts of spring: bubbly streams, glassy puddles, wiggly worms, shiny beetles, crocuses and apples buds and blades of grass and squishy mud. By the time a vee of ducks fly in to join her, the ice is melting, and the little duck dives into spring. With many wonderful repetitions of consonant sounds — quick quick quick, blink blink blink, creak creak creak — the book is a delight to read aloud.

Cold Little Duck Duck Duck by Lisa Westberg Peters, with illustrations by Sam Williams, tells a rhythmic and rhyming story of a duck who comes a little too early in a miserable and frozen spring, and her feet freeze to the ice. She warms herself with thoughts of spring: bubbly streams, glassy puddles, wiggly worms, shiny beetles, crocuses and apples buds and blades of grass and squishy mud. By the time a vee of ducks fly in to join her, the ice is melting, and the little duck dives into spring. With many wonderful repetitions of consonant sounds — quick quick quick, blink blink blink, creak creak creak — the book is a delight to read aloud.

And, like the cold little duck duck duck, we might be finding spring right now as well. The snow outside my window has almost melted, the first wildflowers are blooming, and our hearts are happy in the sunshine. Good work, ducks. Thanks, thanks, thanks!