Why do we love chicken stories so much? Perhaps it’s because chickens are approachable heroes in stories that we can learn from or laugh with. We have long had the serious hard-working Little Red Hen, the silly Henny Penny, prideful Chanticleer.

It is our feeling that we can never have enough chicken stories. Chickens can also be where we find whimsy or better versions of ourselves. Today we want to enjoy some more recent chicken stories.

The chickens in Chickens on the Loose by Jane Kurtz are off for adventure. In a Youtube read-aloud Jane Kurtz tells us the story was inspired by the chickens in her neighborhood in Portland, Oregon, who occasionally visited her yard.

Written in rollicking rhyme — “Chickens on the loose, racing down the street / Hopping up to window shop clinging with their feet” — the story follows this lively flock all over Portland — shop, yogi studio, diner. At each stop the person in charge calls out “Stop!” And, as in the Gingerbread Man, they all join in pursuit of the chickens. But the chickens do not stop … Until … well you’ll have to read the story.

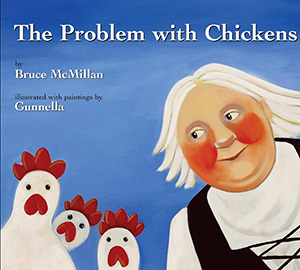

The chickens in Bruce Macmillan’s The Problem with Chickens do not run all over. They do what chickens should do, lay eggs. The ladies of the village had gone to town to buy them because the ladies had no eggs, not being able to collect eggs from the birds who nest on the cliffsides. And all went well for a while. The chickens laid many eggs. The ladies used them “for cooking and the cakes were delicious.” But, oh no, “That is when the problems started. The chickens forgot they were chickens. They started acting like the ladies.” They went along on the blueberry picking, attended birthday parties with the ladies, joined them in singing to the sheep. “The chickens were so busy acting like ladies that one day they stopped laying eggs.”

The chickens in Bruce Macmillan’s The Problem with Chickens do not run all over. They do what chickens should do, lay eggs. The ladies of the village had gone to town to buy them because the ladies had no eggs, not being able to collect eggs from the birds who nest on the cliffsides. And all went well for a while. The chickens laid many eggs. The ladies used them “for cooking and the cakes were delicious.” But, oh no, “That is when the problems started. The chickens forgot they were chickens. They started acting like the ladies.” They went along on the blueberry picking, attended birthday parties with the ladies, joined them in singing to the sheep. “The chickens were so busy acting like ladies that one day they stopped laying eggs.”

What do the ladies do? They begin to exercise, and the chickens do, too. Every day the ladies and the chickens exercise until arms, legs, and wings are strong. When the ladies lift them into the air and say, “Remember, you are birds,” the chickens fly off and land on the sides of Icelandic cliffs. But these ladies are now strong and not deterred by cliffsides.

This book is a delight. The ladies are not fazed by chicken problems. Illustrator Gunnella’s ladies are sturdy and practical — and not without their own whimsy.

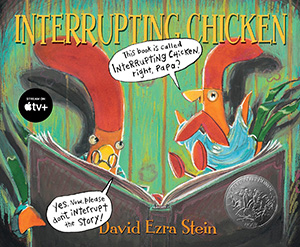

We expect that chickens have no care about human conversation, so an “interrupting chicken” is perfectly charming. And in the book Interrupting Chicken, by David Stein, the interrupter is a young chicken whose father is reading bedtime stories. The young chicken promises not to interrupt but really must tell Hansel and Gretel that the old lady inviting them into the house made of candy cannot be trusted. Another promise not to interrupt but Little Red Ridinghood must be warned not to talk to strangers (especially wolf strangers). After one more interruption Papa Chicken gives up and says, “You tell me a story.” He does not interrupt but promptly falls asleep. This story would be a wonderful read aloud.

We expect that chickens have no care about human conversation, so an “interrupting chicken” is perfectly charming. And in the book Interrupting Chicken, by David Stein, the interrupter is a young chicken whose father is reading bedtime stories. The young chicken promises not to interrupt but really must tell Hansel and Gretel that the old lady inviting them into the house made of candy cannot be trusted. Another promise not to interrupt but Little Red Ridinghood must be warned not to talk to strangers (especially wolf strangers). After one more interruption Papa Chicken gives up and says, “You tell me a story.” He does not interrupt but promptly falls asleep. This story would be a wonderful read aloud.

If, like we do, you love Interrupting Chicken and her papa and want more of her exuberant take on stories, read Little Red Chicken and Cookies for Breakfast and Little Red Chicken and the Elephant of Surprise.

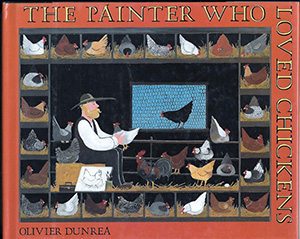

In The Painter Who Loved Chickens by Olivier Dunrea, a painter who lives in the city dreams of a farm in the country — a farm with chickens. He loves painting chickens, but people only want to buy pictures of people, poodles, or penguins. Whenever the painter has a little extra time, though, he paints his beloved chickens. Finally one day he can’t paint another portrait, poodle, or penguin. He can’t even paint another chicken, and so he paints … an egg. A woman comes in to buy a picture, falls in love with the egg painting, and offers the painter a large amount of money. When the painter protests she explains that she’s been looking a very long time for such a picture. Encouraged, the painter shows her his paintings of chickens that no one else had wanted to buy, and the lady purchases them all with a check large enough for the painter to buy his country farm and, of course, his own flock of chickens. From then on, he only paints what he loves, and the lady comes to the farm often to visit the chickens, buy more chicken paintings, and take home eggs. You could argue that the lady is a kind of convenient outside force that rescues the painter, but it’s his dedication to painting what he loves that is the real saving grace. A reminder to us all that doing whatever we love — painting chickens, buying pictures of chickens, planting gardens, writing stories — is what will make us happy.

In The Painter Who Loved Chickens by Olivier Dunrea, a painter who lives in the city dreams of a farm in the country — a farm with chickens. He loves painting chickens, but people only want to buy pictures of people, poodles, or penguins. Whenever the painter has a little extra time, though, he paints his beloved chickens. Finally one day he can’t paint another portrait, poodle, or penguin. He can’t even paint another chicken, and so he paints … an egg. A woman comes in to buy a picture, falls in love with the egg painting, and offers the painter a large amount of money. When the painter protests she explains that she’s been looking a very long time for such a picture. Encouraged, the painter shows her his paintings of chickens that no one else had wanted to buy, and the lady purchases them all with a check large enough for the painter to buy his country farm and, of course, his own flock of chickens. From then on, he only paints what he loves, and the lady comes to the farm often to visit the chickens, buy more chicken paintings, and take home eggs. You could argue that the lady is a kind of convenient outside force that rescues the painter, but it’s his dedication to painting what he loves that is the real saving grace. A reminder to us all that doing whatever we love — painting chickens, buying pictures of chickens, planting gardens, writing stories — is what will make us happy.

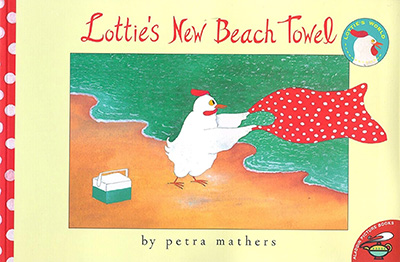

The late Petra Mathers wrote several books about Lottie, a chicken. In Lottie’s New Beach Towel a red polka-dotted beach towel arrives with a note: Dear Lottie, this might come in handy this summer. Love Aunt Maddie. The beach towel does come in handy in so many ways. Lottie is meeting her friend Herbie (a duck) at the beach for a picnic, but as she walks to the water the hot sand burns her feet. Solution: hopscotching from picnic cooler to beach towel to picnic cooler to beach towel all the way down to the cooling water to meet Herbie in his boat.

When the boat’s motor unexpectedly dies on the way to Pudding Rock, Lottie’s towel makes a handy sail, and when the wind steals a bride’s veil at a nearby wedding, the beach towel makes a lovely substitute. After the post-wedding party Lottie and Herbie head home in a boat whose motor obligingly starts. Lottie ends the day by writing Aunt Maddie about all the adventures the beach towel has had.

We love the simplicity of a day spent with a friend and the many ways that a beach towel comes in handy. Petra Mathers said of Lottie, “Lottie is my role model. Even though it seems that I am inventing her, she already exists in all of us when we are at our best.” Editor Laura Geringer said of Mathers, “My home is filled with her joyful artwork, a daily inspiration, and a reminder to relish the colorful absurdities in life.”

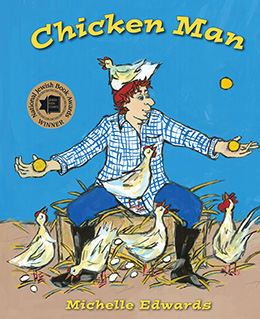

The hero of The Chicken Man by Michelle Edwards is not a chicken but a man, Rody, who lives on a kibbutz in Israel and tends the chickens. He loves the chickens and they love him. Clara even lands on his head and hugs his kibbutz hat. When he tends them they lay more eggs. He makes it look like so much fun that Bracha, the cookie-baker, thinks tending chickens would be much better than the hot kitchen. On the kibbutz the workers are moved from job to job and so is the Chicken Man. At each of his jobs — the laundry, the garden, the children’s house — he does his work cheerfully, makes the best of his situation. Others see him and think that the job he is working at will be more fun, easier, than the job they are working at. But he misses the chickens — and they miss him. They stop laying eggs. No eggs for cookies, no eggs for cake. no eggs to sell. In an emergency work meeting the members agree that the kibbutz needs eggs and the chickens need Chicken Man. So Chicken Man must return to the chicken house. All is well when he returns to the coop — each hen lays an extra egg, and Chicken Man is home.

The chickens are the backdrop for the cheerful Chicken Man who shows us all that a job done with good cheer always looks like fun.

Perhaps these stories, like Petra Mathers’s Lottie, help us all to be our chicken best.

If you would like to read Petra Mathers’ obituary, you can find it here.