Books have been a part of Vaunda Micheaux Nelson’s life since the day she was born. “My mother found my name in a novel she was reading,” Nelson says. Books and family and history form a thread through many of Nelson’s award-winning picture books.

We want to focus on Nelson’s telling of history beginning with the nineteenth century. Almost to Freedom (Carolrhoda, 2003; illustrated by Colin Bootman) is narrated by Sally, a doll made by the little girl Lindy’s enslaved mother for her daughter. “I started out no more’n a bunch of rags on a Virginia plantation,” the doll tells us. When the doll is given to Lindy, Lindy hugs her hard, names her Sally, and says, “We gonna be best friends.” Lindy takes Sally everywhere, tying her to her waist with a rope when Lindy and her momma pick cotton.

We want to focus on Nelson’s telling of history beginning with the nineteenth century. Almost to Freedom (Carolrhoda, 2003; illustrated by Colin Bootman) is narrated by Sally, a doll made by the little girl Lindy’s enslaved mother for her daughter. “I started out no more’n a bunch of rags on a Virginia plantation,” the doll tells us. When the doll is given to Lindy, Lindy hugs her hard, names her Sally, and says, “We gonna be best friends.” Lindy takes Sally everywhere, tying her to her waist with a rope when Lindy and her momma pick cotton.

Then Lindy’s father is sold away to another owner for trying to get to Freedom, and Lindy is whipped for asking Massa’s son how to spell her name. One night Lindy’s momma wakes Lindy “when the sun ain’t awake yet,” and they run away, Sally tied to Lindy’s waist, to meet Lindy’s father at the river. Once across the river, they run, then hide in an underground storeroom in a house on the underground railroad. “We almost to Freedom,” Lindy whispers to Sally, but slave catchers are after them, and when they frantically scramble out to run again, Sally falls out of the rope around Lindy’s waist and is left behind in the hidden storeroom. Sally waits alone in the darkness, thinking she might be there “for the rest of her days” until one day a mother and her daughter Willa, escaped slaves, are hidden in the storeroom. Willa, shivering and scared, picks up the doll, names her Belinda, and promises they will be best friends. While the doll misses Sally, she is “mighty glad to be Willa’s doll baby. It’s a right important job.”

In an author’s note Nelson says she was inspired by a collection of Black rag dolls in a folk art museum, about which the guidebook said a few had been found in an Underground Railroad hideout. Nelson thought, “if only these dolls could talk,” and Sally/Belinda does talk to reader, in a voice that makes us care not just about Sally but also about Lindy and her family and, later, Willa and her mother and any people fleeing the horrors of slavery. Collin Bootman’s rich dark paintings capture the story’s emotions, from fear and pain to tenderness and love. While we don’t learn what happens to Sally and her family or Willa and her mother, the book is a story of hope and courage and comfort in the face of the unspeakable evil of slavery and of the longing for freedom and the “right important job” of being loved.

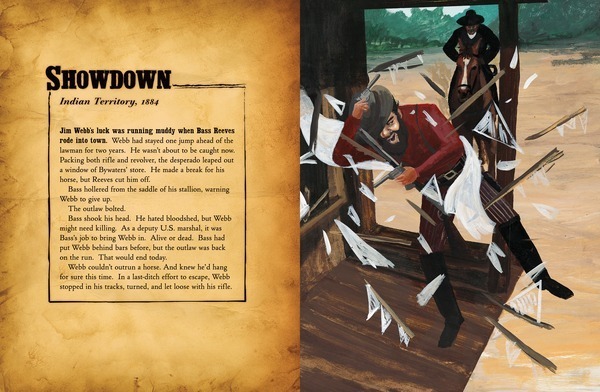

Bad News for Outlaws (Carolrhoda, 2009; illustrated by R. Gregory Christie) begins “Jim Webb’s luck was running muddy when Bass Reeves rode into town.” Muddy, indeed. Webb was on the run from Marshall Bass Reeves and leaped out a window to escape, but Bass chased him down. When Webb fired his gun Reeves, who hated bloodshed, was forced to shoot Webb down. After that dramatic showdown scene, Nelson tells us how Reeves went from enslaved to becoming a legendary lawman in what was then called Indian Territory, a wild part of the wild west.

Bad News for Outlaws (Carolrhoda, 2009; illustrated by R. Gregory Christie) begins “Jim Webb’s luck was running muddy when Bass Reeves rode into town.” Muddy, indeed. Webb was on the run from Marshall Bass Reeves and leaped out a window to escape, but Bass chased him down. When Webb fired his gun Reeves, who hated bloodshed, was forced to shoot Webb down. After that dramatic showdown scene, Nelson tells us how Reeves went from enslaved to becoming a legendary lawman in what was then called Indian Territory, a wild part of the wild west.

Reeves had been enslaved in Texas, where his owner taught him to shoot and hunt. When Bass and his owner argued and Bass hit the owner, Bass knew he had to run, and run he did for Indian Territory, where he lived with Native Americans until slavery ended. Eventually Reeves became a U.S. Marshall for Judge Isaac C. Parker. Reeves was known for tracking down criminals and also for his shooting ability, so accurate he could “‘shoot the left hind leg off a contented fly sitting on a mule’s ear at a hundred yards and never ruffle a hair.’”

Never taught to read, Reeves memorized everything he needed to know to hunt down wanted outlaws, often using disguises to capture them. In his long career he arrested more than three thousand people and brought in wagonloads of criminals. Both respected and hated, Reeves was “right as rain from the bootheels up” and devoted to doing his duty. Once he cut down a man about to be lynched by an angry mob, an act that was “near as risky as a grasshopper landing on an anthill.” When Bass Reeves’s son killed his wife, Bass did his painful duty and arrested his own son.

For 32 years, Bass Reeves hunted down outlaws and brought them in to face justice. He was the longest serving marshal in Indian territory until Oklahoma became a state and Reeves was out of a job. Nearly seventy years old, he joined a local police force, and during his two years on the force not a single crime occurred in his area. Such was the power of Reeve’s reputation as a lawman. When he died, fellow lawmakers called Reeves one of the bravest men the country had ever known and “the most feared deputy U.S. marshal that was ever heard of.”

Reading this book is a joy, both for the story of Bass Reeves and also for the voice in which Nelson tells that story. Extensive back matter includes an author’s note, definitions for “western words” such as shooting irons and tumbleweed wagons, a timeline of Reeves’s life, suggestions for further reading, and historical background on Indian Territory and the life of Judge Isaac C. Parker.

In Dream March (Random House, 2017; illustrated by Sally Wern Comport), Vaunda Micheaux Nelson adds a book to Random House’s Step into Reading History Reader Series and tells the story of the 1963 March on Washington.

In Dream March (Random House, 2017; illustrated by Sally Wern Comport), Vaunda Micheaux Nelson adds a book to Random House’s Step into Reading History Reader Series and tells the story of the 1963 March on Washington.

Nelson is not content with the bland style occasionally found in easy readers and offers wonderful details for the march. “Some walked over 200 miles from Brooklyn, New York. One man rolled 698 miles from Chicago on skates. It took him ten days.” She shares lyrics from some of the songs sung that day. And she skillfully lets readers know what was at stake. “Black people fought/for many years/for the right to be treated/with respect…They fought for the right/to attend the same schools/and eat in the same restaurants. /They fought to use/the same bathrooms/and drink from the same/water fountains. /They fought to sit /on any empty bus seat/and to have the same chance/at a job. /They fought for the right to vote./”

To be treated with respect…the right to vote. The fight is not over. But we can take courage from this moment, this event. Nelson reports on Martin Luther King Jr.’s stirring words: “Finally Martin said, / his voice like thunder: /’Let freedom ring!’ /’From every hill’ and/‘every mountainside,’ /’from every state and every city,’ /’let freedom ring!’ /And if we do, people/of all colors and all faiths/will join hands and sing: /’Free at last, free at last,/thank God Almighty,/we are free at last!’”

We two like to think of young readers learning of this historic event through Vaunda Micheaux Nelson’s carefully chosen words. Perhaps they will never forget the man who roller skated to attend. Perhaps they will be the people of all colors who join hands and sing. Let us hope.

We have always thought that books give us neighbors we never would have had otherwise. And Vaunda Micheaux Nelson puts readers from a small town in Iowa or south Minneapolis right next to an amazing bookstore in Harlem — the National Memorial African American Bookstore.. Lucky us!

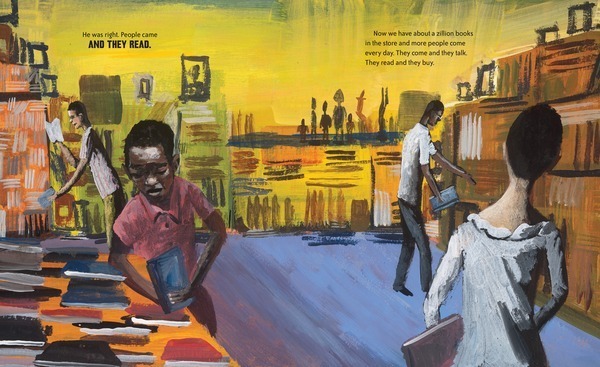

Her story The Book Itch: Freedom, Truth & Harlem’s Greatest Bookstore (Carolrhoda, 2015; illustrated by R. Gregory Christie) introduces us to her great-uncle Lewis Michaux, a self-educated man who wanted to provide books for African-Americans who lived in Harlem. She has also written a book about this store for older readers. In this younger version she tells her great-uncle’s story through the voice of his son, Lewis Michaux Jr., who she says provided much information about Lewis Michaux Sr. and his store.

Her story The Book Itch: Freedom, Truth & Harlem’s Greatest Bookstore (Carolrhoda, 2015; illustrated by R. Gregory Christie) introduces us to her great-uncle Lewis Michaux, a self-educated man who wanted to provide books for African-Americans who lived in Harlem. She has also written a book about this store for older readers. In this younger version she tells her great-uncle’s story through the voice of his son, Lewis Michaux Jr., who she says provided much information about Lewis Michaux Sr. and his store.

Lewis Michaux’s store eventually became famous and was visited by celebrities such as Muhammed Ali and Louis Armstrong, civil rights leaders such as W.E.B. Dubois and Malcolm X, and hundreds of Harlem residents. But in the beginning when Lewis Michaux went to a bank to ask for a loan, the bank refused. “The banker told him ‘Black people don’t read.’”

Lewis persisted and raised money for the store by washing windows. He acquired more and more books until the store was jammed full of books, wall to wall, top to bottom. “Customers stay as long as they want, even if it’s past closing time. Dad never makes them leave like other stores do. Sometimes Dad locks up so late he’s too tired to come home. He sleeps there with all his books.” Lewis Michaux loved signs: “Knowledge is power. You need it every hour. Read a book!” “Don’t get took. Read a book.” Some of his best signs are reproduced in the endpapers of the book.

Lewis also hosted speakers for rallies outside his bookstore. Whenever they set up the raised platform “people crowd around.… People come to hear talk about fighting for the same rights white people have. Talk about jobs and voting. People shout angry words. They kid around and laugh.…Dad talks to the crowd from the platform too. He says black people need to learn their history by reading books.” Lewis Michaux was friends with Malcolm X who spoke outside the store, received his mail at the store, and often talked with the bookstore owner.

The most moving section of this book reports the assassination of Malcolm X. The civil rights leader was scheduled to speak at the Audubon Ballroom and Michaux was going to appear onstage with him. But Michaux was late because he had to pick up his son from ice-skating with friends at Rockefeller Center.

“Mom hangs up [the phone] and looks at me. ‘Malcolm…’ Her eyes are wet. She can’t talk for a minute. ‘Someone shot him when he stood up to give his speech.

I can’t breathe.

Later I hear Dad’s key in the door. He hugs Mom and me and sags into his chair. …

After I go to bed, Dad sits in the living room, crying in the dark. I never heard Dad cry before, and I don’t know what to do. I can’t keep from crying too…

Malcolm used to say, ‘If you’re not willing to die for it, put the word freedom out of your vocabulary,’ Dad said. ‘They think they got rid of him. But people won’t forget, Louie. His words will never leave us.’

Lewis Michaux Sr.’s own grief about Malcolm X takes us right to the scene of his death. We feel its impact because we already know Lewis Michaux and we care about him.

“His words will never leave us.” The story ends by noting the importance of words and the importance of books and the “National Memorial African Bookstore.”

Backmatter information tells us that the bookstore was forced to move in 1968 because of the construction of a new state office building. (Why on this particular site? Could it have something to do with the importance of words and books?) Lewis moved the store and a few years later he “received notice from the state that he was being evicted.”

We are so grateful for this book (Get a new look. Read a book.) and the glimpse into the life of this remarkable man who followed his dream to make books available to the people of Harlem, to provide a gathering place for his people to promote the exchange of words and ideas.

Nelson writes like a poet, and her language sings. Dolls and lawmen, booksellers and civil rights activists, enslaved people fleeing for freedom, ordinary people marching in Washington D.C. — all of them come alive in her books. Here are other titles of hers to read and learn from and delight in.

I love Vaunda’s books! Thank you for featuring her work.

We love her, too, and eagerly await another book.

I shared your column with Vaunda, and after she saw your column, she subscribed to Bookology!

A well deserved recognition of an author who cares about her subjects and does meticulous research.

Thanks for reading. Vaunda Micheaux Nelson’s back matter could be the basis for a course in how to write back matter for non-fiction books for kids.

I loved the much deserved article on Vaunda Micheaux Nelson! Over the years, Vaunda has written books about real life situations, that reach the hearts of readers, both young and old. Her books, regarding black historical figures, contributes much to the education of people of all races, and creates a sense of pride in our black children.

We loved sharing her books. And you are so right – her books are satisfying and enriching for readers of all ages.

I am thrilled to see such an insightful look at the glorious work of my very dear friend and writing group colleague of over 20 years, Vaunda Micheaux Nelson. Your article is written with care and loving attention, so it really honors Vaun’s rich body of work.