Jackie: After Phyllis and I read Amos and Boris for our last month’s article on boats we both wondered why we hadn’t looked at the work of William Steig. He so often executes that very satisfying combination of humor and heart. Steig’s language is funny but his stories regularly involve worrisome separation and then return to a loving family.

Jackie: After Phyllis and I read Amos and Boris for our last month’s article on boats we both wondered why we hadn’t looked at the work of William Steig. He so often executes that very satisfying combination of humor and heart. Steig’s language is funny but his stories regularly involve worrisome separation and then return to a loving family.

William Steig was born to immigrant Jewish parents from Eastern Europe in 1907. His father was a painter and decorator and his mother was a seamstress. When the Depression came, Steig supported the family by selling cartoons to The New Yorker magazine. At age sixty he began to write children’s books and wrote more than two dozen before his death in 2003 at age 95.

Roger Angell, writing in The New Yorker, quoted a New York school teacher [his wife] speaking about Steig’s children’s books: “They’re touching but not sentimental, and they bring young children ideas they’ve not experienced before.”

They’re touching and they are funny — sometimes they are downright silly. In Solomon The Rusty Nail (1985), Solomon the rabbit figures out that if he scratches his nose and wiggles his toes at exactly the same time he becomes a rusty nail. Not to worry, this is not Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, not yet at least. Solomon also figures out that if he says to himself, “I’m no nail, I’m a rabbit,” he will quickly become a rabbit again.

They’re touching and they are funny — sometimes they are downright silly. In Solomon The Rusty Nail (1985), Solomon the rabbit figures out that if he scratches his nose and wiggles his toes at exactly the same time he becomes a rusty nail. Not to worry, this is not Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, not yet at least. Solomon also figures out that if he says to himself, “I’m no nail, I’m a rabbit,” he will quickly become a rabbit again.

Phyllis: I thought I knew most of Steig’s work but I didn’t know this book, and I love it, not least for Steig’s wonderfully playful language. When Solomon discovers his ability to transform, his first thought is to show his family what a “prize pazoozle of a rabbit” he is but decides instead to keep his “secret secret.” When Solomon transforms into a rusty nail behind a tree to fool a cat who has captured him, the cat is “discombobulated “and searches for Solomon “clockwise, counter clockwise, and otherwise.”

But for all their delicious language, Steig’s stories have high stakes: when Solomon refuses to turn back into a rabbit so the cat and his wife can eat him, the irate cat pounds him into the wall of their cabin where Solomon, unable to transform back into his true self, wonders, “Do nails die?”

Jackie: Steig’s Doctor DeSoto, (1982) the mouse dentist has always been a favorite of mine. It is the perfect combination of humor and sensitivity, even compassion. Even though he has sworn not to treat foxes and wolves, Doctor Desoto agrees to treat the suffering fox. And the fox repays this kindness by wondering if it would be “shabby” to eat Dr. and Mrs. DeSoto. [Is “shabby” not the perfect, hilarious word here?] We root for Doctor DeSoto who says he always finishes what he starts and we love his remarkable preparation that allows him to fix the fox’s tooth and save the lives of him and his wife.

Jackie: Steig’s Doctor DeSoto, (1982) the mouse dentist has always been a favorite of mine. It is the perfect combination of humor and sensitivity, even compassion. Even though he has sworn not to treat foxes and wolves, Doctor Desoto agrees to treat the suffering fox. And the fox repays this kindness by wondering if it would be “shabby” to eat Dr. and Mrs. DeSoto. [Is “shabby” not the perfect, hilarious word here?] We root for Doctor DeSoto who says he always finishes what he starts and we love his remarkable preparation that allows him to fix the fox’s tooth and save the lives of him and his wife.

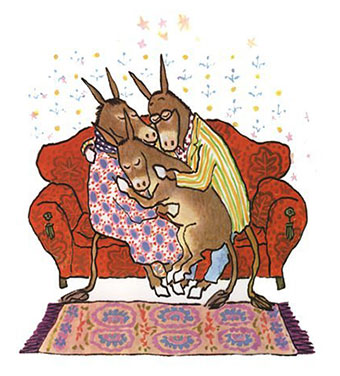

Perhaps everyone knows Sylvester and the Magic Pebble (1969), Steig’s Caldecott winner. Sylvester’s unfortunate wish turns him into a rock. His parents grieve. He sits and drowses as a rock until a remarkable series of circumstances results in his return to his old donkey form. So satisfying.

Steig loved this theme of transformation and clearly wasn’t done with it after Sylvester. He gave us the above-mentioned Solomon the Rusty Nail, The Toy Brother (1996), Gorky Rises (1980), all of which involve some sort of magical preparation or incantation and some sort of “stuckness.”

Phyllis: Steig is a master at making us believe these seemingly inexplicable vicissitudes. In The Amazing Bone Pearl the pig finds a bone that can talk in any language and imitate any sound — a trumpet’s call to arms, the wind blowing, the rain pattering down, snoring, sneezing. When Pearl asks the bone how it can sneeze, it replies, “I don’t know. I didn’t make the world.” When a hungry fox captures Pearl and the bone pleads for him to let her go, the fox replies, “I can’t help being the way I am. I didn’t make the world.”

Phyllis: Steig is a master at making us believe these seemingly inexplicable vicissitudes. In The Amazing Bone Pearl the pig finds a bone that can talk in any language and imitate any sound — a trumpet’s call to arms, the wind blowing, the rain pattering down, snoring, sneezing. When Pearl asks the bone how it can sneeze, it replies, “I don’t know. I didn’t make the world.” When a hungry fox captures Pearl and the bone pleads for him to let her go, the fox replies, “I can’t help being the way I am. I didn’t make the world.”

Jackie: The Toy Brother (1996) is a wonderful turnaround book about two siblings who live with their parents — Magnus Bede, a famous alchemist, and his “happy-go-lucky wife” Eutilda. The older son, Yorick, “considers little Charles a first-rate pain in the pants.” Yorick is his father’s apprentice and hopes to turn donkey dung into gold. When the parents go off for a wedding Yorick sneaks into his father’s lab. Things don’t work out as he hoped and Yorick next appears the size of a mole. Charles enjoys his role as big brother and is actually kind to Yorick, builds him a house, feeds him crumbs of cheese, tries to amuse him by costuming himself and the family animals. But the two cannot get Yorick back to his original size, and neither can Magnus. Until Yorick remembers one very important detail.

Jackie: The Toy Brother (1996) is a wonderful turnaround book about two siblings who live with their parents — Magnus Bede, a famous alchemist, and his “happy-go-lucky wife” Eutilda. The older son, Yorick, “considers little Charles a first-rate pain in the pants.” Yorick is his father’s apprentice and hopes to turn donkey dung into gold. When the parents go off for a wedding Yorick sneaks into his father’s lab. Things don’t work out as he hoped and Yorick next appears the size of a mole. Charles enjoys his role as big brother and is actually kind to Yorick, builds him a house, feeds him crumbs of cheese, tries to amuse him by costuming himself and the family animals. But the two cannot get Yorick back to his original size, and neither can Magnus. Until Yorick remembers one very important detail.

Once again, Steig’s language is such a joy. When they realize what is needed, Magnus says, “Ginger! That’s a fish from another pond. Is it any wonder there was no transmogrification?” What child is not going to love that? I almost feel transmogrified reading it.

Gorky the frog makes a potion, too, in a kitchen lab, with “a little of this and a little of that: a spoon each of chicken soup, tea, and vinegar, a sprinkle of coffee grounds, one shake of talcum powder, two shakes of paprika, a dash of cinnamon, a splash of witch hazel, and finally a bit of his father’s clear cognac and a lot of attar of roses (!!).”… “This obviously was the magic formula he had long been seeking.”

Gorky the frog makes a potion, too, in a kitchen lab, with “a little of this and a little of that: a spoon each of chicken soup, tea, and vinegar, a sprinkle of coffee grounds, one shake of talcum powder, two shakes of paprika, a dash of cinnamon, a splash of witch hazel, and finally a bit of his father’s clear cognac and a lot of attar of roses (!!).”… “This obviously was the magic formula he had long been seeking.”

He doesn’t know what it will do but soon realizes that it enables him to rise in the sky and float. He startles the groundlings, including a fox who looks like he just dropped by before his gig in Doctor DeSoto. Gorky endures a storm and longs for home…and eventually figures out how to get there.

Phyllis: In Amos and Boris, I was startled by the fortuitous appearance of two elephants who help Amos the mouse roll Boris the whale back into the sea when he is beached by a storm. I didn’t realize that more elephants wander through Steig’s stories — Elephant Rock where Gorky eventually lands really is a transformed elephant, restored to his real self by the last drops of Gorky’s formula.

Phyllis: In Amos and Boris, I was startled by the fortuitous appearance of two elephants who help Amos the mouse roll Boris the whale back into the sea when he is beached by a storm. I didn’t realize that more elephants wander through Steig’s stories — Elephant Rock where Gorky eventually lands really is a transformed elephant, restored to his real self by the last drops of Gorky’s formula.

Storms are also recurring characters in Steig’s books. Irene encounters a storm in Brave Irene, an inimitable one that yodels a warning: “Go home….GO HO-WO-WOME,” as she attempts to deliver a dress her mother has made for the duchess. When the wind carries off the dress, Irene presses on in the worsening storm to tell the duchess what happened to her beautiful gown. Irene twists her ankle, she gets lost, night falls, she shivers from the cold, and just when she finally spots the castle below she is swallowed by a snowdrift up to her hat. In despair, she wonders if she should give up and freeze to death, since she is already buried. But the memory of her mother “who always smelled like fresh-baked bread” gives her the energy to fight free of the snowdrift, find a way to the castle (where the wind has plastered the gown to a tree) and eventually arrive home, driven by the doctor who tells her mother “what a brave and loving person Irene was. Which, of course, Mrs. Bobbin knew. Better than the duchess.”

Storms are also recurring characters in Steig’s books. Irene encounters a storm in Brave Irene, an inimitable one that yodels a warning: “Go home….GO HO-WO-WOME,” as she attempts to deliver a dress her mother has made for the duchess. When the wind carries off the dress, Irene presses on in the worsening storm to tell the duchess what happened to her beautiful gown. Irene twists her ankle, she gets lost, night falls, she shivers from the cold, and just when she finally spots the castle below she is swallowed by a snowdrift up to her hat. In despair, she wonders if she should give up and freeze to death, since she is already buried. But the memory of her mother “who always smelled like fresh-baked bread” gives her the energy to fight free of the snowdrift, find a way to the castle (where the wind has plastered the gown to a tree) and eventually arrive home, driven by the doctor who tells her mother “what a brave and loving person Irene was. Which, of course, Mrs. Bobbin knew. Better than the duchess.”

Jackie: These characters are all surprised by circumstance. Storms fly in. The potions do not work exactly as planned. Dealing with these circumstances is not always easy. And so it is with the lives of children. Things do not go along as planned. They hear: “We are moving. You’ll be going to a new school.” “Your father and I are separating.” “We’re having a new baby. You’ll need to share your room.” It’s hard to get back to the old life. That is true in Steig’s stories. Sylvester’s parents grieve when they lose him. Gorky’s parents search for him all night and are tremendously relieved to see him.

All of his characters are returned to the loving arms of family, changed perhaps by their adventures, but not alone. I would love to do a session with students in which we read these books and then wrote our own story of transmogrification. What a freeing experience to change into something/someone else, to float, to talk to a bone — that talked back.

Phyllis: What a terrific idea. I want to read all of his books aloud, savoring his deliriously delectable language in book after book after book. Steig is a prize pazoozle of a writer as well as an artist.

Jackie: Though he was not writing tracts for children Steig was well aware of the power of story. He said in his Caldecott Acceptance Speech:

Art, including juvenile literature, has the power to make any spot on earth the living center of the universe, and unlike science, which often gives us the illusion of understanding things we really do not understand, it helps us to know life in a way that still keeps before us the mystery of things. It enhances the sense of wonder. And wonder is respect for life. Art also stimulates the adventurousness and the playfulness that keep us moving in a lively way and that lead us to useful discovery.

Books for children are something I take seriously. I am hopeful that more and more the work I do for children, as well as the work I do for adults, will approach the condition of art. I believe that what this award and this ceremony represent is our mutual striving in the same direction, and I feel encouraged by the faith you have expressed in me in honoring my book with the Caldecott Medal. (Caldecott Acceptance Speech, June, 1970).

His stories remind us that the “mystery of things … stimulate[s] adventurousness and playfulness” in both theme and language. In Steig’s books we can share the fun of sound, the joy of adventure, and the sweetness of return.

Phyllis: And they remind us, too, that in the inexplicable events of the universe, our families love us, search for us when we are lost, and welcome us home again with immeasurable delight.

See also: The Collection of William Steig at the University of Pennsylvania.

What a fantastic visit to Mr. Steig’s magical worlds. His books exhibit the adventure and danger every child wants while never denying readers the kindness & security every child needs. Brava!

I’m now desperate to get to the library to learn about that rusty nail/rabbit. Thank you for illuminating Steig’s work. His work should continue to influence writing today.