As a reporter and editor for decades, I often heard people accuse my colleagues and me of “bias,” of having a particular slant on a story — usually a point of view that the accuser disputed. It was a common charge, especially if the issue was controversial.

But in truth, reporters are no different than anyone else. Everyone comes to a subject with some kind of bias. If you know what a certain beach is like, then you are likely to associate other beaches with that experience; if you’ve never been to the beach, then you can only imagine what the smells, the sand, or the sea is like.

If you are pro-candy, you will read about candy differently than someone who doesn’t like it.

When you write nonfiction, these different reader perspectives matter. If we want to be thoughtful about a subject or apply those all-important critical thinking skills, it helps to acknowledge our natural biases — not to judge, but simply to understand that our experiences affect how we see things.

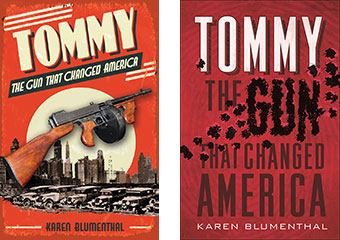

When I speak to junior high students, I often hold up a copy of my book Tommy: The Gun that Changed America and ask them what they think it is about.

When I speak to junior high students, I often hold up a copy of my book Tommy: The Gun that Changed America and ask them what they think it is about.

“Why would I write this,” I go on, “and why, especially, for young people?” Then I might show them the paperback version, which has the same title, of course, but no gun on the cover. “What do you make of that?”

From there, we can actually start talking about guns — what role they play in our society, what makes them interesting to readers and how they generate strong feelings — without having to debate the Second Amendment.

Because we live in such a visual world, I spend hours tracking down the right photos, cartoons, and documents to help tell a story. And even if these images don’t make it into the book, they influence my writing by reminding me what the world looked like and how people felt in that time period.

The images that do make it into my books can change the reader’s experience, challenging the biases they bring to the story.

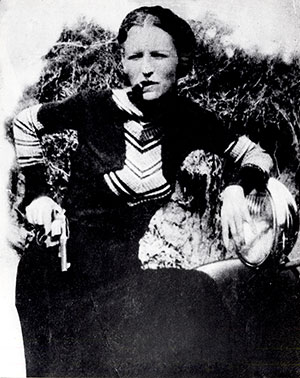

Consider this photo of Bonnie Parker, a key image in my next book, Bonnie and Clyde: The Making of a Legend, due out in August 2018. It’s a crucial picture, the first time she became known to the public. What do you think about her when you see this? What do you think she’s like?

Now compare it to the glamour shot below, taken just a few years before. Does it change your perspective at all?

Maybe one way to make student research and nonfiction more engaging is to consider our assumptions and biases by bringing images into the process. Some ideas:

of the Dallas History and Archives Division

of the Dallas Public Library)

- Ask students to make assumptions about a book from the cover. Then compare to what the story is inside. Did their perspective change?

- Pull out a single image and try to guess what it means to the story. Then, read that chapter (or picture book) and test it.

- Ask students to search for a photo separately from their research on a subject. Did the photo enforce or change their point of view?

What other ways can you address how a reader’s experiences can impact understanding?

Wow — what startling differences between the two photos of Bonnie Parker, and what a great way to make your point!