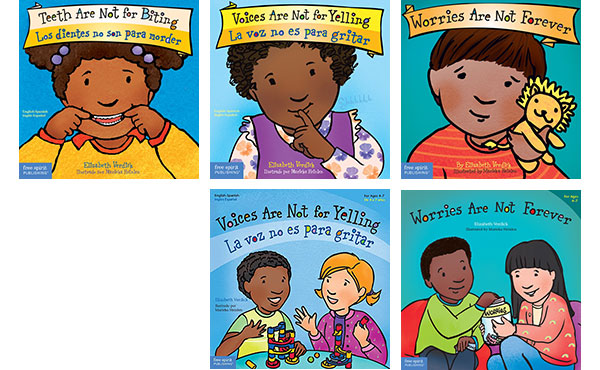

Back when my kids were little, I started work on a nonfiction SEL (Social and Emotional Learning) series called the “Best Behavior” series. More than a decade later, these board books and paperbacks are still going strong, I’m happy to say. Titles in the series include Teeth Are Not for Biting, Voices Are Not for Yelling, and Worries Are Not Forever. The books are about shaping behavior, but in a deeper sense, they’re designed to help young children express their feelings, get their needs met, and better understand their growing independence. I think of my books as tools in an SEL toolkit. They can help you bring out the best in children during the toddler years, all the way through early elementary school, and beyond.

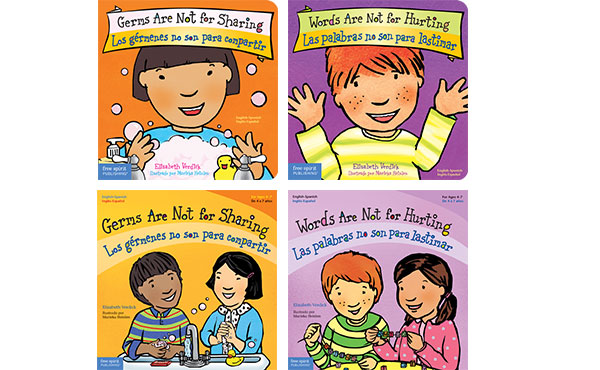

My goal from the beginning of the series was to use simple words to teach, encourage, and reassure young children. But I realized that my toddler board books — limited to 11 spreads, with one full spread devoted to tips for parents and educators — were too short to fully cover the topics for a wider audience. What a toddler can understand from a book called Germs Are Not for Sharing is much different from what a preschooler or kindergartner can grasp. So, I’ve created more in-depth paperbacks for older children, using the same titles as the board books. I have various versions of, for example, Words Are Not for Hurting: the board book, the expanded paperback, and Spanish/English versions of both. It’s been a joyful challenge for me to adapt my words to the different ages and stages children go through. I love aging down and aging up! The process is great practice for any writer, new or experienced, especially if you want to write for children.

How do you age down your text? First, know that aging down is very different from “writing down to children.” Our goal as children’s writers is not to write to children in babyish language or to lecture our readers, even in books that aim to guide a child’s behavior. Whether you’re aging your text down or up, respect young readers’ intelligence; know that they feel fiercely and they care deeply. E. B. White said it this way:

“Children are … the most attentive, curious, eager, observant, sensitive, quick, and generally congenial readers on earth.”

Some children’s writers take the approach of getting all their ideas and best lines on the page first, so they don’t get caught up in editing themselves too much, too early. In other words, they write long before writing short. This method feels expansive and freeing; it lets you use the page to explore and brainstorm. Yet, there are some tips to keep in mind so you’ll be on your way to creating work that’s age appropriate. Expert picture-book writer Anne Whitford Paul in her manual Writing Picture Books says there are characteristics of children to keep in mind as you write for them, including:

Some children’s writers take the approach of getting all their ideas and best lines on the page first, so they don’t get caught up in editing themselves too much, too early. In other words, they write long before writing short. This method feels expansive and freeing; it lets you use the page to explore and brainstorm. Yet, there are some tips to keep in mind so you’ll be on your way to creating work that’s age appropriate. Expert picture-book writer Anne Whitford Paul in her manual Writing Picture Books says there are characteristics of children to keep in mind as you write for them, including:

- Children have had few experiences.

- Children have strong emotions.

- Sometimes childhood is not happy.

- Children long to be independent.

- Children are complicated.

Paul’s list is actually longer, and I highly recommend getting a copy of her helpful manual (recently revised and updated) if you want to write for young kids. Let the children in your own life inform your writing, too. Spend time listening to them closely, soaking in their words and creative turns of phrase. Ask children to read aloud to you — paying close attention to what captures their imaginations and resonates with them emotionally. Invite fellow writers to read and comment on your work: What age group do you think this is for? Is this too wordy? Where might I cut some text?

Suppose you’ve written a manuscript for very young children, but you’re not sure if it’s age appropriate. The easiest place to start is with a word count. General guidelines suggest that manuscripts should be 500 words or less. If you’re writing for toddlers, much less. Think of it this way: Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown is only 130 words. For fun, I just counted the words in my toddler board book Voices Are Not for Yelling: 131. Fiction picture books for young children, including Goodnight Moon, are often brief, poetic texts in which every word matters—sometimes described as “Perfect words in perfect places.” Nonfiction books for little ones are similarly short but are often designed to give information or share a message. In my SEL nonfiction, I don’t aim to be poetic but do hope to share simple phrases children can use on their own every day:

“You are bigger than your worries.”

“Teeth are not for biting. Ouch, biting hurts.”

“Warm water, lots of soap, scrub, scrub, scrub. Send those germs down the drain.”

I adore writing short! It’s satisfying for me to pick at my own words like I pick weeds in my garden. I’m an editor at heart, and that’s where I got my start in publishing, helping other writers use language to the best of their abilities. When writing for the very young, revise and then revise again (and again) to boil down your language to its simplest form. If that sounds difficult or boring, remember that illustrations do half the work in books for little ones. A simple tip? Get rid of your adjectives or overly descriptive language. Illustrations can do that job for you.

Whenever I’m starting a new book in the “Best Behavior” series, I tackle the board book first. This helps me simplify the concepts and language for the youngest audience, while also letting me reach the finish line faster. Once I’ve written the board book, I feel like I’ve accomplished something and want to do more. I then think of the ways in which preschoolers, kindergartners, and older children experience behavior issues in school and in the community. As they grow older, children spend more time outside of the home, engaging with a wider variety of people and places. A child’s world gradually expands — and so my books have to expand as well. But not by too much. I try to keep that “500 words or less” rule of thumb firmly in mind as I write.

Recently, I visited a first-grade classroom to share a couple of my picture books, Small Walt (about a little snowplow) and Peep Leap (about a baby wood duck afraid to leave the nest). A theme in each of these works is “small can be mighty” and that we all need encouragement, from ourselves and others. One of my favorite lines in Peep Leap is: “You are braver than you know.” To be honest, I feel scared every time I start a new manuscript. It doesn’t matter how many books I’ve written before — each new one feels like a challenge I have no idea how to take on. I give myself little pep talks and reach out to fellow writers who often feel the same way. On that day of the first-grade visit, the teacher pulled me aside and confided that she had a book idea and wanted to write for children and hadn’t started yet because it felt too “big.” Well, I hope she does start writing soon, and I told her to give it a try. If you work with children or are raising them, you have an insider’s view into what makes kids tick, and how much they grow and change as time rolls on. That’s a great start … now you need to put some words on the page.

Recently, I visited a first-grade classroom to share a couple of my picture books, Small Walt (about a little snowplow) and Peep Leap (about a baby wood duck afraid to leave the nest). A theme in each of these works is “small can be mighty” and that we all need encouragement, from ourselves and others. One of my favorite lines in Peep Leap is: “You are braver than you know.” To be honest, I feel scared every time I start a new manuscript. It doesn’t matter how many books I’ve written before — each new one feels like a challenge I have no idea how to take on. I give myself little pep talks and reach out to fellow writers who often feel the same way. On that day of the first-grade visit, the teacher pulled me aside and confided that she had a book idea and wanted to write for children and hadn’t started yet because it felt too “big.” Well, I hope she does start writing soon, and I told her to give it a try. If you work with children or are raising them, you have an insider’s view into what makes kids tick, and how much they grow and change as time rolls on. That’s a great start … now you need to put some words on the page.