In my three decades as a professional author, I’ve written about many intriguing, accomplished people: the Wyeth family of artists, painter Georgia O’Keeffe, abolitionist Lucretia Mott, author Peter Mark Roget, poets William Carlos Williams and Marianne Moore, self-taught artist Horace Pippin, inventor Louis Braille, and most recently Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright August Wilson. In every case, I’ve focused my research on the words and the work of the subject themselves and have created what I hope are poetic and accessible books about these important men and women for young readers.

When I choose a biographical topic (or rather, when the topic chooses ME, as it more often seems to do!) it’s because I’m fascinated about the details of the person’s life, their struggles, triumphs, discoveries, and, yes, their failures. Fascinated to the point of obsession, which is a GOOD thing, because all of these people have BIG lives which require months and months of research to comprehend. They have friends, families, pets, colleagues, jobs, and schools. Many of them excel in multiple fields. The Thesaurus author Peter Mark Roget, for example, was a physician, a public health advocate, a mathematician (he invented a slide rule and a portable chess set), an expert in optics and botany. The blind inventor Louis Braille was a gifted organist who was hired by some of the largest churches in Paris. Georgia O’Keeffe held teaching positions in various schools before she found her spiritual home in the desert of New Mexico.

But you won’t find most of those details in the books I wrote. In researching every life story, there are inevitably dozens of people, events, and achievements that must be left out. That is hard! When an author uncovers an interesting tidbit or an as-of-yet-unknown aspect of her subject’s life, her impulse is to write it all down and display it like a shiny object on the long shelf of the book’s narrative.

However … part of being a picture book biographer is zeroing in on just one or two threads of the subject’s life, and twisting them together in a lyrical way so that young readers get a clear, sharp sense of the person. Too many details muddy the waters, and therefore it’s not uncommon for chunks of carefully researched and written text to be left out of the final manuscript (but often these CAN be included, albeit in a less lyrical way, in the back matter of the book.)

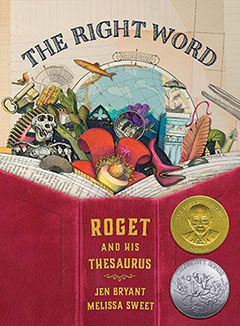

One good example is a scene I wrote into the narrative of The Right Word: Roget and his Thesaurus (Eerdmans, 2014, illustrated by Melissa Sweet). When Peter Roget graduated medical school, he was only 17 years old — too young to become a professional doctor. He needed to fill a few years with other activities while he matured. So he took a position as a language and literature tutor to two teenage sons of a wealthy Scottish businessman. Roget’s job was to travel with them through France and Switzerland, helping them to learn the customs, languages, geography, etc.

One good example is a scene I wrote into the narrative of The Right Word: Roget and his Thesaurus (Eerdmans, 2014, illustrated by Melissa Sweet). When Peter Roget graduated medical school, he was only 17 years old — too young to become a professional doctor. He needed to fill a few years with other activities while he matured. So he took a position as a language and literature tutor to two teenage sons of a wealthy Scottish businessman. Roget’s job was to travel with them through France and Switzerland, helping them to learn the customs, languages, geography, etc.

This sounds like a lot of fun, but it was also the time of the Napoleonic Wars between France and England, and Roget’s age and nationality made him vulnerable to capture and conscription. At one point, Roget and his young charges were trapped in a mansion in Switzerland, with no apparent way to escape. With the help of a flirtatious and well-connected Swiss countess, Roget and the boys were able to travel at night, disguised, through the city where they were staying and on into Germany, where they caught a ship and sailed safely back to the U.K.

Fun stuff to research and to write about — and it certainly would have been a LOT of fun for Melissa Sweet to illustrate! The problem was that it just didn’t move the center of the story forward in any helpful way, a fact that was pointed out to me by EBYR editor Kathleen Merz. She was absolutely right. The threads of the Roget narrative were all about LANGUAGE — how it could be collected, savored, shared and used by anyone everywhere, and how a shy, obsessive young man made it his mission to try and catalogue language and ideas in a single, practical book. This scene was a side adventure, and despite its dramatic details, was an unnecessary part of the text. We took it out (but it is noted in the timeline in the back matter) and that decision made the final book better than it would have been otherwise.

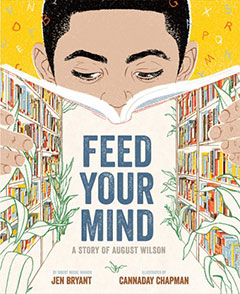

With my latest book, I want kids to learn about, and to love, August Wilson. That’s my goal.

With my latest book, I want kids to learn about, and to love, August Wilson. That’s my goal.

There is so much that gets left out, and yet all of that other research informs the book somehow and makes it richer: he had older sisters and younger brothers, and friends and roommates, he joined the Army for a while, he had a deep father-son-like friendship with director Lloyd Richards, he was married three times and had two daughters—all of that will be included, I’m sure, in a comprehensive adult biography of August Wilson. I believe a theater critic is working on one to be published in the future.

And much of that is listed in the back matter of my book, but it’s not the focus. The focus is on how did Freddy find his voice, and how did he teach himself to write plays.

So — I’m coming from it through my own love of language, my own curiosity about the creative process. This is what I’ve done with seven other picture book biographies (O’Keeffe, Messiaen, Moore, William Carlos Williams, Pippin, Roget, Braille, about creative people and one novel (Pieces of Georgia).

It’s good to hear from a pro about something I’ve just started doing (PB biographies). Thank you.

Jen, so interesting to here these background stories to your writing process. Your books are wonderful avenues into fascinating lives!

Thank you, Jen ~ so well explained. (PS the nonfiction panel you were on at USIBBY in Austin was the standout of the conference for me);

Oops…I meant USBBY /IBBY