The heavy hush inside my hometown’s public library in Superior, Wisconsin, felt lushly laden with the promise of knowledge and stories, all organized in tidy card catalogs and shelved row by row within the Carnegie brownstone. I breathed its velvety silence, its reverence interrupted only by muffled coughs and murmured politeness. I loved it from the first moment my mother brought me along as a preschooler while she browsed for books.

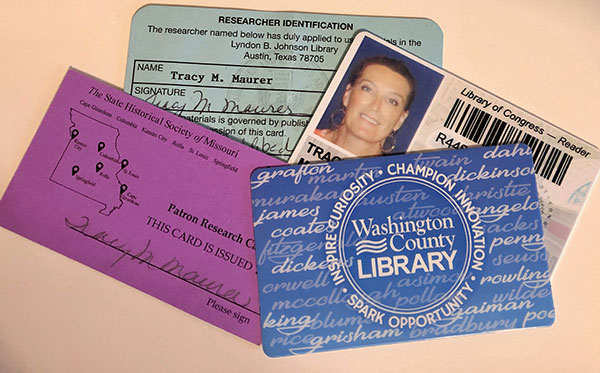

first discovered the wonderful power of a library card, circa 1980. Used with permission.

Then one day in 1970, Mom walked me down a long staircase to the library’s basement for a surprise: the children’s section! When the library was built in 1902, the section was upstairs, although a dedicated children’s librarian wasn’t hired until 1909. This was forward thinking for the times. Spaces for young readers were rare in America’s small towns until well into the 1900s. Our children’s library moved down to the basement in 1932 due to the growing adult section. By the time of my first visit, it smelled musty and looked shoe-horned into the space. I didn’t care. Shelves at my height held more books than I could count — all for young readers like me!

My heart leapt when I learned that I was old enough for my first library card — the key to that vast kingdom of words. I’ve treasured each library card since then. I studied journalism at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis and spent countless hours in the libraries there. Earning my master’s degree in writing for children and young adults from Hamline University in St. Paul introduced to me to specialty collections, particularly the Kerlan Collection within the Children’s Literature Research Collections at the University of Minnesota. Original manuscripts and artwork there reveal fascinating pathways to publication, including those of internationally famous Minnesota authors like Kate DiCamillo and Wanda Gág.

Writing more than 100 nonfiction books for children over the years has given me wonderful opportunities to explore rare book and specialty collections across the United States for research.

I reviewed historic diaries and personal notes at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University for my book, Noah Webster’s Fighting Words.

I visited the New York Public Library Special Collections twice for more book research. The second time, the librarian greeted me as if we were old friends — of course, she had access to all of my application and identification materials required before each visit, but I appreciated the gesture.

I saw (and touched!) pages from John J. Audubon’s massive folio of Quadrupeds of North America at the Amherst College Rare Book Holdings in Massachusetts.

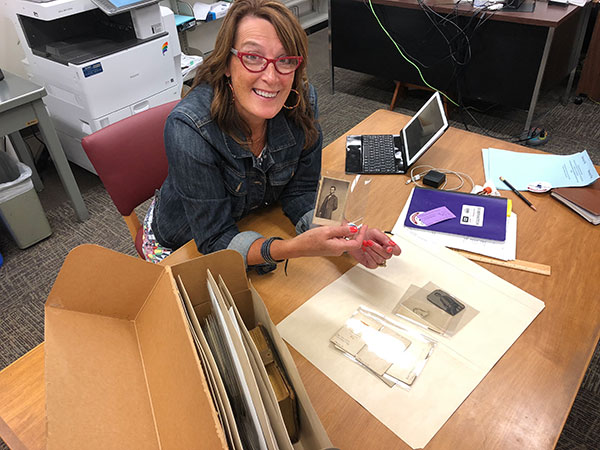

At the State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center at Springfield, I held cartes de visite, calling-card sized photographs popularly collected in the mid 1800s. One card was signed by President Grant and another by President Lincoln.

held in the archives at the State Historical Society of Missouri.

As a side-trip during a 2019 conference in Washington, D.C., my colleagues and I received the most amazing personal tour by Sybille Jagusch, Chief Librarian of the Children’s Literature Center of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division of the Library of Congress (THE Library of Congress!).

at the Library of Congress, discusses original artwork

and manuscripts during a special tour of the facility in 2019.

at the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library in Austin, Texas.

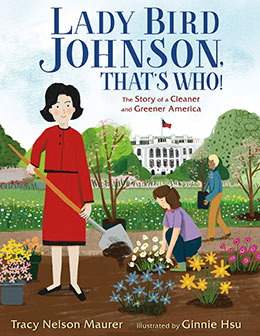

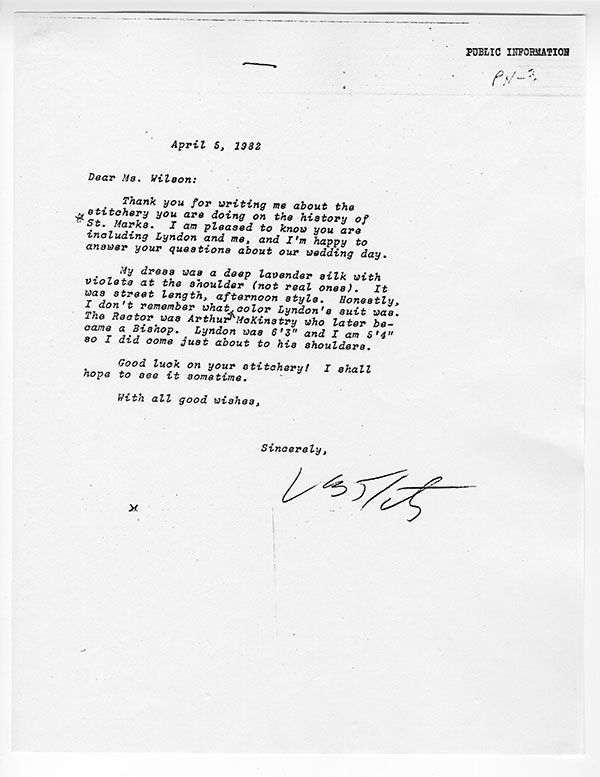

Most recently, I spent a lot of time at the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library in Austin, Texas, to complete some research for my newest book, Lady Bird Johnson, That’s Who! (illustrated by Ginny Hsu, published Feb. 23, 2021). I read Lady Bird’s letters and speeches, studied hundreds of photographs, and asked the archivist a barrage of questions — even after I was home. For example, when my editor questioned the illustrator’s depiction of the Johnson wedding, I sent the archivist the inquiry. What did Lady Bird really wear? The archivist promptly emailed back with a photocopy of a letter (a primary source — the holy grail of research), in which Lady Bird wrote, “My dress was a deep lavender silk with violets at the shoulder (not real ones). It was street length, afternoon style.” Bingo!

Most recently, I spent a lot of time at the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library in Austin, Texas, to complete some research for my newest book, Lady Bird Johnson, That’s Who! (illustrated by Ginny Hsu, published Feb. 23, 2021). I read Lady Bird’s letters and speeches, studied hundreds of photographs, and asked the archivist a barrage of questions — even after I was home. For example, when my editor questioned the illustrator’s depiction of the Johnson wedding, I sent the archivist the inquiry. What did Lady Bird really wear? The archivist promptly emailed back with a photocopy of a letter (a primary source — the holy grail of research), in which Lady Bird wrote, “My dress was a deep lavender silk with violets at the shoulder (not real ones). It was street length, afternoon style.” Bingo!

such as this letter from Lady Bird Johnson, to authenticate their nonfiction work.

The beauty of all these incredible experiences? They happened at libraries, open to anyone with a research question, at no charge. Treasure your local public library. Support it however you can — donations, check-outs, participation in programs. These hard-working institutions and their librarians welcome everyone, rarely with the hush-hush I recall from my youth. Whether in-person or online in these COVID times, your library reveals information, opens minds and, sometimes, touches your heart.

This is great. We love libraries and they have been a life-line during the pandemic. The ways that they’ve gotten creative to continue offering resources and programs throughout the past year has made our lives richer.

A wonderful ode to libraries from a terrific author!

Libraries have provided me with a lifetime of happy memories, from the eagerly awaited annual Summer Reading Club when I was growing up to checking out audiobooks as an adult to help me on long road trips. What a great tribute this was!