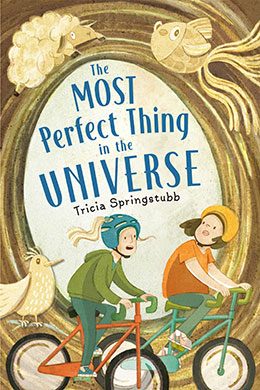

Loah Londonderry, hero of my new middle grade novel, The Most Perfect Thing in the Universe, is the daughter of a noted ornithologist dedicated to saving endangered birds of the Arctic tundra.

Loah Londonderry, hero of my new middle grade novel, The Most Perfect Thing in the Universe, is the daughter of a noted ornithologist dedicated to saving endangered birds of the Arctic tundra.

That sentence contains four words that, when I started writing, I knew little about: ornithologist, endangered, and Arctic tundra.

Uh oh.

I’ve never been a fan of research. I prefer to make stuff up, and even when my world-building demands facts, my first, lazy inclination is to fudge my way through. With this book, though, I had to knuckle down.

Unlike nonfiction writers who dive into extensive research, I looked for facts to give my story the ring of truth. I already knew that the Arctic is warming at a rate nearly twice the global average. Now I needed to understand more about how changing climate patterns endanger wildlife and how conservationists struggle to protect threatened species. Because my book centers on Loah, not her mother, I didn’t try to understand everything (as if I ever could!). Instead, I found facts that added to the story’s emotional complexity and gave poor Loah a difficult conflict. While she appreciates the urgency and importance of Dr. Londonderry’s environmental work, she also deeply misses her mother, whose expeditions take her away for months at a time. She fears her mother loves birds more than her.

I’d imagined the tundra as a desolate place. Instead, books and online conservation sites had me swooning over its stark winter beauty and blazing spring brilliance. I fell in love with caribou and musk ox. I discovered the Arctic tern, which makes a yearly migration from one polar region to the other and back, a round trip of about 25,000 miles. I learned that, in contrast to the tern, some birds never stir far from the nest where they hatch. I loved the parallel with Dr. Londonderry and her bold expeditions and homebody Loah.

Again and again, I found my research connecting with my story — or was my fiction connecting to my research? I’m still not sure. I do know that one of the book’s themes became that each of us defines home in our own way, and that every home is precious. When Loah most needs help, she finds connection and support in new friends, a happy echo of the ecological interdependence of all living things.

The title was another gift of my research. It’s drawn from the words of the nineteenth-century naturalist Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who wrote, “I think that, if required on pain of death to instantly name the most perfect thing in the universe, I should risk my fate on a bird’s egg.” (Leave off those last three words, and you have a very fun writing prompt!)

It was immensely reassuring to be fact-checked by an ornithologist from the American Museum of Natural History. He had some trouble with the fictional bird I created, and I squirmed a little over verifiable truths vs. poetry, but we worked it out.

Though the book is finished, my interest in birds and the environment is keener than ever. What a treat to recently read about the reappearance of a black-browed babbler, a bird that, like the fictional one in my book, had not been seen for decades and was feared extinct! Ornithologists are jubilant – me too.

Nature has its mysteries, and so does the writing process, where facts and imagination can twine together in ways lovely and unexpected. Maybe next time I won’t be so reluctant to begin my research…

I enjoyed this article so much! Can’t wait to try your writing prompt on some kids I know and I’m excited to read/share your book with my birding family.

Thanks, Connie! Happy birding, happy reading!