Enter the freshman chemistry tutor dressed in torn jeans and a flannel shirt. His job? To get me through entry level chemistry at Iowa State University. My first college plan was to major in Hotel and Restaurant Management because my father owned a company that did business with these types of institutions. So, what the heck, I didn’t know what else to study so I declared that my major way back in the fall of 1977.

No one told me that since these kinds of institutions serve food, I had to take courses in food and nutrition. And since food and nutrition were science based, I must take chemistry. Three quarters of chemistry! Ugh. Back to the tutor’s and my results; C+, and that was after a lot of hard work. My new major; journalism and mass communications, and forty years later the stars have aligned. Science is drawing me in now.

No one told me that since these kinds of institutions serve food, I had to take courses in food and nutrition. And since food and nutrition were science based, I must take chemistry. Three quarters of chemistry! Ugh. Back to the tutor’s and my results; C+, and that was after a lot of hard work. My new major; journalism and mass communications, and forty years later the stars have aligned. Science is drawing me in now.

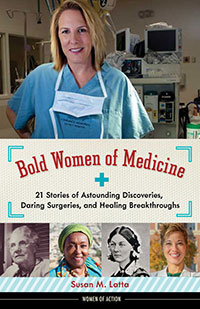

When I wrote the proposal for Bold Women of Medicine, it did not occur to me that I would have to write about science. Well … what did you think, Susan? Write about these courageous doctors, nurses, midwives, and physical therapists, and there wouldn’t be any science? Oh, dear. I flashed back to freshman chemistry and biology, and suspected I was in big trouble.

When I wrote the proposal for Bold Women of Medicine, it did not occur to me that I would have to write about science. Well … what did you think, Susan? Write about these courageous doctors, nurses, midwives, and physical therapists, and there wouldn’t be any science? Oh, dear. I flashed back to freshman chemistry and biology, and suspected I was in big trouble.

Along the way I discovered that not having this knowledge was a good thing, and in my case, it almost helped me. I could write from a position of innocence and explain the women’s medical careers without a condescending tone to my readers: I was one of those readers.

Take for example one of the women in my book, Helen Taussig and her part in treating the blue baby syndrome. I barely knew how the human heart worked when it was healthy, and now I’d have to explain how brilliant medical researcher Mr. Vivien Thomas, and Drs. Taussig and Blalock, discovered how to fix the defect. (Hint: Vivien Thomas practiced on hundreds of dogs, the most famous of which is Anna, whose portrait hangs at Johns Hopkins Hospital.)

Off to the library I went to check out books on the human heart — first adult books, then books for children. I studied the healthy heart and heart defect jargon and tried to explain it to myself first, and then write it down. Fortunately, I have medical professionals in my life so, after a few drafts, I had them read it to see if I had explained it correctly and without intense medical language. Did you know the normal child’s heart is about the size of their fist? I didn’t know that.

Off to the library I went to check out books on the human heart — first adult books, then books for children. I studied the healthy heart and heart defect jargon and tried to explain it to myself first, and then write it down. Fortunately, I have medical professionals in my life so, after a few drafts, I had them read it to see if I had explained it correctly and without intense medical language. Did you know the normal child’s heart is about the size of their fist? I didn’t know that.

The tiny babies were not getting enough oxygen and in Dr. Taussig’s mind the fix seemed to be a simple case of improved plumbing. The narrative tension was built right into the story. Specifics always work better so I wrote about the first operation on one of the babies, little Eileen Saxon, and later another operation on a six-year-old boy.

In the profiles of Dr. Catherine Hamlin and Edna Adan Ismail, the science writing was more challenging knowing my audience was young adult (12 and up). Writing about medicine automatically lends itself to topics we don’t want to hear about — in this case, FGM (Female Genital Mutilation) and Obstetric Fistula. One young woman came to Dr. Hamlin for help by walking almost 280 miles. Ten years earlier, because of a prolonged labor, she had suffered two holes in her bladder (an obstetric fistula) and lost all control. At first Dr. Hamlin did not know how to help her, but she talked to other physicians and studied up on procedures. After the successful surgery, Dr. Hamlin presented the young woman with a new dress in which to go home. The woman waved good-bye with hope and said “God will reward you for all you have done for me.” Presenting the image of an optimistic woman with a new dress helps readers understand Dr. Hamlin’s important work.

As I wrote about science for the first time, I learned a few things along the way:

- Every famous surgery or discovery or treatment has a story. Find that story, find the human part of that story.

- Character, setting, and the five senses can help science dribble into the story.

- Keep your wonder and gross-out mindset alive. Kids possess this mindset naturally and many appreciate the guts (no pun intended) of the details.

- There are no stupid questions when interviewing experts. Be curious, and if you can, experience the science first-hand.

- Know that your audience is smart, just inexperienced in the subject.

- Double (and triple) check your science writing with the experts. The last thing you want to do is send out incorrect information.

Because the women of medicine were accomplished, it was easy to assume they knew all the answers. They did not … but they were curious and that curiosity led them to answers. Science often comes up with negative results, people just trying to understand how something works. This doesn’t always make the news. Building on these negative results leads scientists to the flashy news and the successes.

I built on my (limited) knowledge, and learned right along with my audience. I had a lot of false starts, not really knowing what I was writing about. Fortunately, for the patients, I never had to actually perform the difficult procedures and surgeries.

And to that chemistry tutor in the flannel shirt, wherever you are: thanks for the help. I probably did learn something. Next up: seismology. Know any good tutors?