I’m fussy when it comes to choosing where to sit. The comfy chair or the well-worn red sofa? Lights on high or nicely dimmed? Soft throw blanket? Sometimes even in a restaurant, I ask to sit at a different table than the one the host chooses because it doesn’t feel right. My husband rolls his eyes.

Setting whether in fiction, nonfiction, or my own family room, holds a special place in my heart. I need to experience the place. Its scent, lighting, sounds, and details. Setting is just as much a character in nonfiction as the people or events we write about. Here are a few tips to make the most of that nonfiction setting.

1. Paint your setting with details:

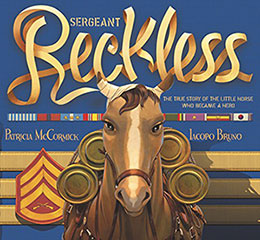

In Sergeant Reckless: The True Story of the Little Horse Who Became a Hero, the author Patricia McCormick begins the story with a problem. The U.S. Marines fighting in Korea are worn out from hauling heavy ammunition to the cannon named Reckless up the hill. They found a small mare and set out to train her. The reader can’t help but be smack dab in the war with the horse now named Sergeant Reckless.

In Sergeant Reckless: The True Story of the Little Horse Who Became a Hero, the author Patricia McCormick begins the story with a problem. The U.S. Marines fighting in Korea are worn out from hauling heavy ammunition to the cannon named Reckless up the hill. They found a small mare and set out to train her. The reader can’t help but be smack dab in the war with the horse now named Sergeant Reckless.

“One day, the marines spotted enemy troops approaching; instantly, they went into battle mode. Pvt. Monroe Colman saddled up Reckless and led her to the top of the hill. BOOM! Just as they were delivering their load, the cannon went off. A blast of hot air sent dust and gravel flying toward the horse. Reckless jumped straight in the air — even with six shells on her back…BOOM! The cannon roared again. She jumped, but not so high this time. BOOM! This time, Reckless just snorted. By the next time the gun went off, Reckless was busy eating a helmet liner she’d found in the grass.”

The scene got my heart racing, as if I were right there. And after the danger, my heart swelled with admiration for both the marines and Sergeant Reckless.

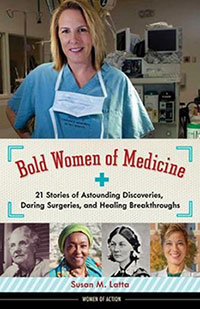

In my YA nonfiction book, Bold Women of Medicine: 21 Stories of Astounding Discoveries, Daring Surgeries, and Healing Breakthroughs, Dr. Catherine Hamlin arrives in Ethiopia: “The fresh scent of eucalyptus mixed with dust in every breath reminded them of Australia. Someone was supposed to have met them. When no one arrived … they walked along the fragmented road carrying their luggage and seeing nothing but green countryside, loaded-down donkeys, and a few cars.” Details help to provide the backdrop for this setting.

In my YA nonfiction book, Bold Women of Medicine: 21 Stories of Astounding Discoveries, Daring Surgeries, and Healing Breakthroughs, Dr. Catherine Hamlin arrives in Ethiopia: “The fresh scent of eucalyptus mixed with dust in every breath reminded them of Australia. Someone was supposed to have met them. When no one arrived … they walked along the fragmented road carrying their luggage and seeing nothing but green countryside, loaded-down donkeys, and a few cars.” Details help to provide the backdrop for this setting.

2. Use all five senses:

Smell brings to mind all kinds of places; a zoo, a cup of bleach in a laundromat. Sounds like; a ringing bell, chugging train, or the hum of a crowded market add to the setting. Light; how it brightens a gloomy day. Touch: the soft warm blanket on a cold night, the silkiness of your dog’s coat.

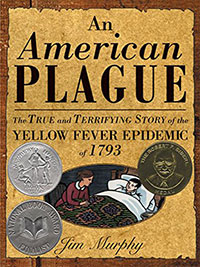

The beginning of An American Plague by Jim Murphy uses the sense of smell combined with other details to draw the reader in. Sight and sound are familiar senses many writers use. But smell is sometimes even more effective.

The beginning of An American Plague by Jim Murphy uses the sense of smell combined with other details to draw the reader in. Sight and sound are familiar senses many writers use. But smell is sometimes even more effective.

“Saturday, August 3, 1793. The sun came up, as it had every day since the end of May, bright, hot, and unrelenting. Dead fish and gooey vegetable matter were exposed and rotted, wild swarms of insects droned in the heavy, humid air.”

The book pulls us in immediately with the weight of the air and forces the reader to feel unease. And in the following passage the sensory words he uses such as clattered, squawking, and squealing add to the uncertainty.

“Horse drawn wagons clattered up and down the cobblestone street, bringing in more fresh vegetables, squawking chickens, and squealing pigs. People commented on the stench from Ball’s wharf, but the market’s own ripe blend of odors — of roasting meats, strong cheeses, days-old sheep and cow guts, dried blood and horse manure — tended to overwhelm all others.”

Surrounding your characters with as many senses as you can help to establish a solid setting. When I read this, I wanted to plug my nose and wipe sweat off my forehead. If your nonfiction is historical, of course you were not there. It helps to visit the location of the event or walk the streets of your subject.

3. Weather:

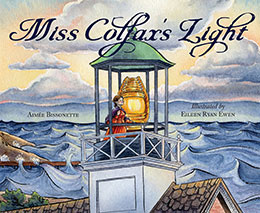

Take full advantage of the weather. A blinding blizzard sets the story. A humid day, we feel the sluggishness of the characters. Crisp fall weather gives us a chill, gets us ready to settle in for the winter. Aimée Bissonette writes about one turbulent night in her picture book biography, Miss Colfax’s Light.

Take full advantage of the weather. A blinding blizzard sets the story. A humid day, we feel the sluggishness of the characters. Crisp fall weather gives us a chill, gets us ready to settle in for the winter. Aimée Bissonette writes about one turbulent night in her picture book biography, Miss Colfax’s Light.

“One stormy night in 1886, when Harriet was more than 60 years old, she set out for the west pier. The wind raged. Driving sleet covered her coat with ice. Sand from the dunes along the lake pelted Harriet’s face, stinging her cheeks. She struggled with her lantern and her bucket…The beacon tower swayed in the wind as Harriet struck her match and lit the light. Teeth chattering from the cold, she hurried back across the catwalk. When she stepped off the catwalk, a deafening screech filled the air. Crash!”

Aimee highlights weather details that incite danger as we move through the scene with Miss Colfax. We feel the ice on our face and the slipperiness under our feet. What will happen, will she slip? This scene gives me both the chills and a shaky stomach.

Back here in Minnesota, it’s getting cold. All the more reason for me to settle in my snug chair lamps dimmed, next to a toasty fire. Steaming cup of tea anyone?

Another excellent piece chock full of good tips!

I love this, Susan. Great information and organization of ideas for writers – young and old. I could easily see teachers using this in their classrooms. I’m inspired by you.