The universal appeal of fairy tales is documented by the similarities of stories across countries, cultures and centuries. The “Cinderella” story alone is over 1000 years old with over 1000 varients. What makes an individual picture book version of a fairy tale unique? The illustrations. Jane Yolen (2004) states, “Many of the picture-book retellings of folktales are more about the art than the story” (p. 43). Illustrators add cultural context and details to the characters and setting, details that are lacking in the text, and the style they choose affects the mood of the story. The list of Caldecott Award books reveals numerous fairy tales. Five stories won the Caldecott Award more than once. What follows in this month’s column and the next is an examination of four fairy tale pairings and one trio to appraise the illustrations that singled out these books as “most distinguished” in a given year.

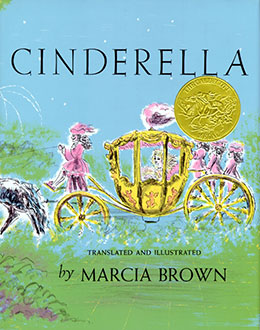

Not only is the Cinderella story “….the best-known fairy tale, and also probably the best-liked” (Bettelheim, 1977, p. 236), Cinderella; or the Little Glass Slipper, translated and illustrated by Marcia Brown, was also the first fairy tale to win the Caldecott Medal in 1955. Brown’s translation of the story is based on Charles Perrault’s familiar version. Perrault lived in 17th century France and told his stories at court, stripping them of anything that might be considered vulgar or offensive to that audience (Bettelheim, 1977). Brown’s Cinderella reflects innocence, goodness, and beauty with golden hair and a soft pastel-colored gown drawn in delicate ink lines. Even the wicked stepsisters, though not beautiful, are always pleasantly smiling.

Not only is the Cinderella story “….the best-known fairy tale, and also probably the best-liked” (Bettelheim, 1977, p. 236), Cinderella; or the Little Glass Slipper, translated and illustrated by Marcia Brown, was also the first fairy tale to win the Caldecott Medal in 1955. Brown’s translation of the story is based on Charles Perrault’s familiar version. Perrault lived in 17th century France and told his stories at court, stripping them of anything that might be considered vulgar or offensive to that audience (Bettelheim, 1977). Brown’s Cinderella reflects innocence, goodness, and beauty with golden hair and a soft pastel-colored gown drawn in delicate ink lines. Even the wicked stepsisters, though not beautiful, are always pleasantly smiling.

Brown did considerable research of that time period to be able to depict the setting and characters realistically through architecture, clothing, and hair styles using gouache, crayon, and watercolors (Commire, 1987). Coiffures of men and women alike are long curly tresses. When the slipper fits and Cinderella is again transformed by her godmother, she fairly glows in an outline of white that adds to the enchantment of this romantic tale.

illustration © Marcia Brown, Cinderella: Or the Little Glass Slipper, Atheneum, 1971

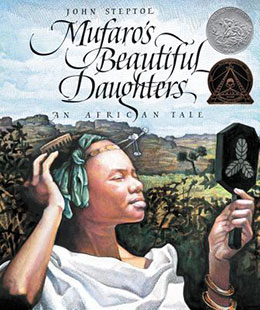

In contrast, Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters: An African Tale takes place in the fields and forests of Zimbabwe. Rather than magical and frilly, the realistic illustrations are vibrant with lush color. The crosshatching technique using ink and watercolor adds texture. John Steptoe wrote and illustrated this Cinderella story based on a Kafir folktale and won a Caldecott Honor in 1988. Mufaro’s two daughters respond to the king’s invitation for all the beautiful young girls to appear before him so he can select a wife. Steptoe’s daughter was the model for both sisters, and the distinction between their personalities, one good and kind, the other selfish and mean, are clear in their facial expressions (Olendorf, 1991).

In contrast, Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters: An African Tale takes place in the fields and forests of Zimbabwe. Rather than magical and frilly, the realistic illustrations are vibrant with lush color. The crosshatching technique using ink and watercolor adds texture. John Steptoe wrote and illustrated this Cinderella story based on a Kafir folktale and won a Caldecott Honor in 1988. Mufaro’s two daughters respond to the king’s invitation for all the beautiful young girls to appear before him so he can select a wife. Steptoe’s daughter was the model for both sisters, and the distinction between their personalities, one good and kind, the other selfish and mean, are clear in their facial expressions (Olendorf, 1991).

illustration © John Steptoe, Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters, Lothrop, Lee and Shepard, 1987

Steptoe researched African history and used the ruins of an ancient city to depict architecture and culture far more advanced and sophisticated than was thought possible in pre-colonial times. His characters are quietly dignified. In his acceptance speech for the 1987 Boston Globe-Horn Book Picture Book Award, Steptoe said, “I wanted to create a book that included some of the things that were left out of my own education about the people who were my ancestors, …. and the more I read, the more reasons I found to be proud.” He chose to write a Cinderella story because it is not just a European tale, and he wanted to show that “industrious, kind, and considerate behavior has always been an ideal to be encouraged.” (Olendorf, 1991, p. 163 – 164).

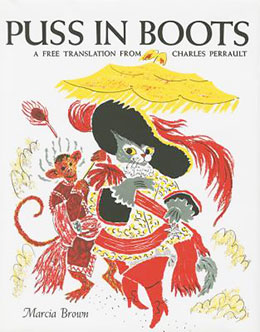

Before she won the Caldecott Medal for Cinderella, Marcia Brown won a Caldecott Honor in 1953 for Puss in Boots, another fairy tale attributed to Charles Perrault. When their father dies, the eldest son inherits the mill, the middle son the donkey, and the youngest son is left only the faithful cat. Despairing how he will survive, the youngest son is rescued by Puss who creates a new identity for him as the Marquis of Carabas. The crafty feline accomplishes this by bullying the peasants, defeating an ogre, and showering the king with gifts from the “marquis.” The king then offers his daughter’s hand in marriage to the young man, and Puss lives out his days as a grand lord.

Before she won the Caldecott Medal for Cinderella, Marcia Brown won a Caldecott Honor in 1953 for Puss in Boots, another fairy tale attributed to Charles Perrault. When their father dies, the eldest son inherits the mill, the middle son the donkey, and the youngest son is left only the faithful cat. Despairing how he will survive, the youngest son is rescued by Puss who creates a new identity for him as the Marquis of Carabas. The crafty feline accomplishes this by bullying the peasants, defeating an ogre, and showering the king with gifts from the “marquis.” The king then offers his daughter’s hand in marriage to the young man, and Puss lives out his days as a grand lord.

Like her Cinderella, Brown’s Puss in Boots reflects the clothing and hairstyles of a similar time period in French history. Using woodcuts and watercolor, she achieves the same effect of wavy hair and ornate carriages. The gowns of both Cinderella and the king’s daughter are remarkably alike with V‑shaped bodices. In Puss in Boots, though, Brown’s palette is not pastels but bold corals, yellows, purples, and grays. Hard at work in his jaunty boots, Puss strides across the pages. He appears in his full courtly regalia including a plumed hat, sash, gloves, and the boots, of course, in a last portrait-like illustration that also appears on the book cover.

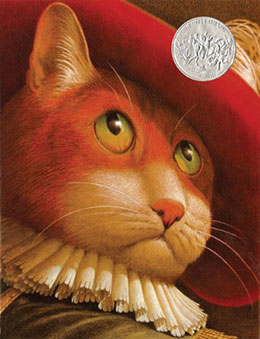

Puss also gazes out from the jacket of the Puss in Boots translated by Malcolm Arthur and illustrated by Fred Marcellino. What is unusual about this jacket is that Puss is all that appears on the front, and it is an extreme closeup showing his face with realistically detailed fur and whiskers, a Renaissance ruffled collar, and part of his hat and jacket. Marcellino’s past career was as a book jacket and album cover designer, and he wanted to create a unique picture book jacket. Considered unconventional at the time, the title and credits appear on the back of the jacket rather than on the front. Marcellino said, “I’ll never be able to do it again; it would completely lose impact the second time around” (Olendorf, 1992, p. 154).

Puss also gazes out from the jacket of the Puss in Boots translated by Malcolm Arthur and illustrated by Fred Marcellino. What is unusual about this jacket is that Puss is all that appears on the front, and it is an extreme closeup showing his face with realistically detailed fur and whiskers, a Renaissance ruffled collar, and part of his hat and jacket. Marcellino’s past career was as a book jacket and album cover designer, and he wanted to create a unique picture book jacket. Considered unconventional at the time, the title and credits appear on the back of the jacket rather than on the front. Marcellino said, “I’ll never be able to do it again; it would completely lose impact the second time around” (Olendorf, 1992, p. 154).

Marcellino designed every aspect of his first picture book, including the old-fashioned font, and he won the 1991 Caldecott Honor for his artistic interpretation. He observed that “… designing a book that has been told and illustrated many times….puts you in a position where everyone who looks at the book will measure you against the past and the way other people have done the book” (Olendorf, 1992, p. 152.) He felt that even though Puss acts rather human, he is always a cat, and that differentiates his book from previous retellings.

Another feature of Marcellino’s art that distinguishes his book is the humor he incorporates. Two frogs look inquisitively at each other as the young man swims in the river, the servant is repulsed by the snake he must serve the ogre, the princess flirts side-eyed with the “marquis,” and the “marquis” acknowledges Puss as he bows to the king and princess. Puss, meanwhile, facing away, nonchalantly leans against a stool with his legs crossed and his paw on his hip.

As did Brown, Marcellino researched the time period to draw the setting and clothing as historically accurate. The colors are muted, and though the scenes seem hazy, the illustrations are very detailed. Using “colored pencil on taupe-textured illustration paper” (ALSC, 2017, p. 117) lends a grainy look that makes some clothing appear to be velvet and adds richness to carpeting. The architecture and the tiled or parquet floors show the influence of Marcellino’s time in Italy as a Fulbright scholar.

Marcellino described his work as “traditional,” but said it also had a “cinematic quality – modern in the sense that the objects are cut off or seen from nontraditional viewpoints” (Olendorf, 1992, p. 154). The vantage point is often a cat’s eye view. But, to add variety, there is a view from below to make the ogre seem more ominous, or from above, as in the two-page spread of the wedding feast. The banquet is across the top of the page with the stairway in the foreground. The banister slants diagonally down to Puss, boots discarded, curled up peacefully in the center of the landing, mission accomplished.

illustration © Fred Marcellino, Puss in Boots, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1990

Having won the Caldecott Award nine times, three medals and six honors, all for fairy tales, folk tales, or fables, Marcia Brown speaks with authority when she states, “When an illustrator attempts the interpretation of a folk or fairy tale that already stands as an entity, the problem of adding a new dimension and bringing the whole into harmonious unity is great. Illustration becomes a kind of visual storytelling in the deepest sense of the word” (Commire, 1987, pp. 33 – 34).

Picture Books Cited

Perrault, C. & Brown, M. (1954). Cinderella: Or the little glass slipper. (M. Brown, Trans.). Antheneum Books for Young Readers.

Perrault, C. & Brown, M. (1952). Puss in boots. (M. Brown, Trans.). Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Perrault, C. & Marcellino, F. (1990). Puss in boots. (M. Arthur, Trans.). Farrar Straus Giroux.

Steptoe, J. (1987). Mufaro’s beautiful daughters: An African tale. Lothrop, Lee & Shepard.

Sources Consulted

Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). (2017). The Newbery and Caldecott Awards: A guide to the medal and honor books. American Library Association.

Bettelheim, B. (1977). The uses of enchantment: The meaning and importance of fairy tales (Vintage Books edition). Random House.

Commire, A. (Ed.). (1987). Brown, Marcia 1918-. In Something about the author (Vol. 47), (pp. 28 – 45). Gale.

Olendorf, D. (Ed.). (1991). Steptoe, John (Lewis) 1950 – 1989. In Something about the author (Vol. 63), (pp. 157 – 167). Gale.

Olendorf, D. (Ed.). (1992). Marcellino, Fred 1939-. In Something about the author (Vol. 68), (pp. 152 – 160). Gale.

Yolen, J. (2004). Once upon a while ago: Folktales in the course of literature. In Pavonetti, L. M. (Ed.), Children’s literature remembered: Issues, trends, and favorite books (pp. 39 – 48). Libraries Unlimited.

I adore Marcia Brown’s Cinderella for its authenticity and delicate beauty. I devoted an entire class on Marcia Brown’s work when I taught my graduate level history of picture book illustrators at Hollins University. I used to buy novels just for the Fred Marcellino jackets. Marcellino was modest, but his work was far from traditional. He painted starlit skies that made me want to make a wish. So glad you brought fairy tales out of the vault!

Fantastic post. I am a teacher trainer for future EFL teachers, and am going to use this! Thank you.