One Step at a Time, One Book at a Time

Introduction

Welcome to the second article in our series, Peace-ology: Finding Higher Ground. In this article we explore the meaning of peacebuilding and what the infrastructure for peace can look like in one classroom and throughout a school. We also suggest a picture book and a book for the “adult on the rug,” both which explore the deep concept of peacebuilding, leaving us with these questions: What peace are you building? Who might be missing from the table?

What is Higher Ground?

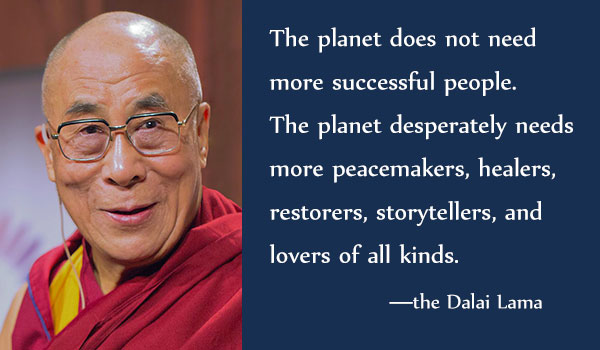

Joyce: The concept of Higher Ground is an ability to move to a higher level of seeing and responding, to grow into a greater awareness of the needs of all so we can act more often on behalf of the greatest good and respond compassionately to the human needs of those different from ourselves. How can we see and respond with greater awareness when we begin to build the infrastructure for peace? That was a burning question I pursued at Eastern Mennonite University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. How can people transform — not solve, not fix — conflicts by building something new between people? Can these concepts be directly applied to our schools and classrooms? Here’s what I learned:

Peacebuilding is about building a new kind of social structure, built collaboratively by a group that shares a new vision and creates new relationships among those involved. In schools, this involves new relationships between school leaders and teachers, teachers and their peers, teachers and students, and students and their peers. It involves a re-working on how people be together and how they learn together.

Peacebuilding is based on an ethic of care. Students need to feel seen and heard by their teachers and acknowledged, valued, and appreciated for who they are and what they contribute to their class community. They also need feedback on what is appropriate and what is not, without being shamed.

Peacebuilding is participatory, empowering everyone involved to make decisions and solve problems. Students build a sense of self-efficacy by seeing their ideas as part of the plan. Teachers also benefit. They not only build closer relationships with their students, but also with one another.

Peacebuilding builds a sense of belonging among students, staff, teachers, and school leaders. The feeling of belonging is something that engenders hope and a sense of agency. Everyone is welcomed at the table. *

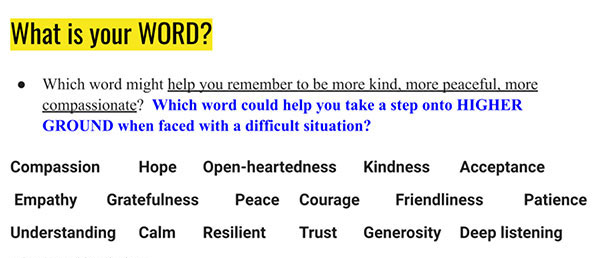

What does it take to begin the process of peacebuilding and sustaining peace in our classrooms and schools? Courage to move forward. Foresight to envision or imagine a peace culture in a classroom or school. Creativity to offer participatory opportunities to build community and a sense of belonging. Inspiration to invite teachers, principals, and student leadership into the work of peacebuilding. Many additional Higher Ground qualities, such as discipline, understanding, kindness, generosity, goodwill, and acceptance also come into play.

How does Renee Dauk-Bleess, art teacher at Oak Crest Elementary become a catalyst for peacebuilding in her 3 – 6 grade classroom and school? Read on.

Creating a Classroom’s Infrastructure for Peace

What is peace?

What kind of person should I be?

Keep pursuing answers to these questions.

—Sachiko Yasui

Renee: These final words, at the very end of Caren Stelson’s young adult nonfiction book Sachiko: A Nagasaki Bomb Survivor’s Story, deeply moved me. Sachiko’s questions were a call to action, urging me to reflect upon the renewed importance of social/emotional learning in the classroom. Thinking about these words was a catalyst for change. Looking back, I realize now Sachiko’s important message was the foundational building block of peacebuilding in my elementary art room.

In the summer of 2020, Caren and I reconnected over her newly published picture book, A Bowl Full of Peace, based on the events from the true story of Sachiko. We spoke of the importance of teaching kindness, peace, and compassion to students, of building relationships with hundreds of students as a specialist teacher, and of developing a culture of peace for an entire school. But how?

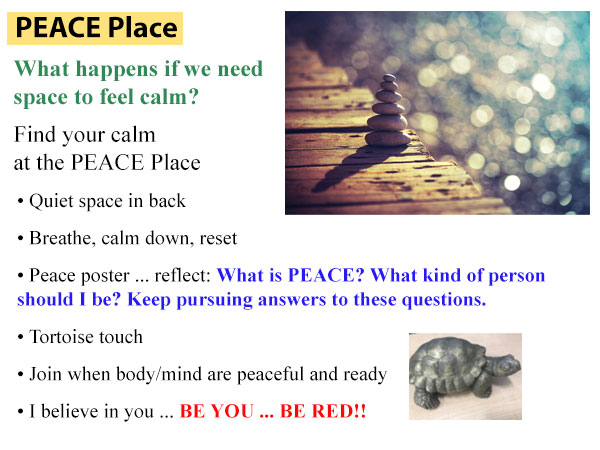

What changes could I make in my Art Room?

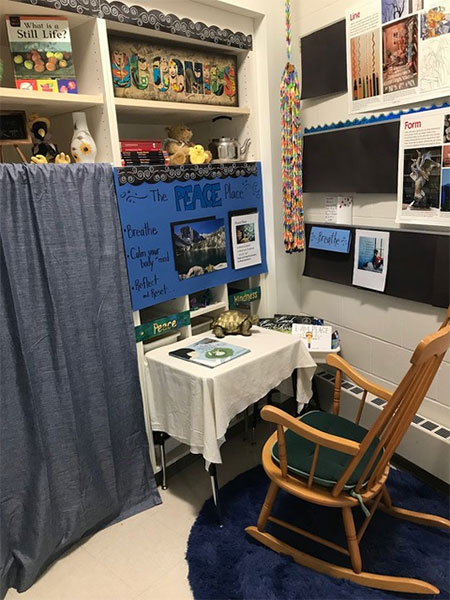

A Physical Space for Peace: I wanted to create a cozy space, a welcoming space in the back of my room — A Peace Place. This was to replace the stark table and chair I put in the corner for a previous “take a break” place. I brought back my grandmother’s rocking chair from the front, (I could no longer gather students together on the rug to read/share/teach due to COVID social distancing requirements) and arranged it in front of a small desk with a tablecloth and soft blue rug underneath. I hung a beautiful poster with calming water and reminders to breathe. I collected a basket of books about peace for students to browse through and read, and posted Sachiko’s questions on the wall. I wanted this to be a place for all students; to let them know that they were welcome in this room and could use the Peace Place at any time.

The Peace Place is also for me. When a difficult behavior issue arises, instead of making a knee-jerk comment or reaction, I simply walk back, rock, and think about peace, what kind of person I want to be, and how to best pursue the answer to that question. Students fall silent; they know that I am doing the work of peacemaking for myself. This powerful act has made such an impact. It has given the Peace Place a genuine, certified value.

The Peace Place is now part of my daily art lesson. When I introduce the Peace Place at the beginning of the year, I model walking back myself and rocking in Grandma’s Chair, explaining it was one of the few things that I had of hers since she passed away almost 40 years ago. A brass tortoise, discovered on a “free” pile, just spoke to me. It is now a beloved part of the Peace Place. Students are encouraged to reach out and touch it, grounding themselves.

Now at the beginning of each art class, as I share the Peace Place slide, I simply raise my hand to invite a student to go back and sit in Grandma’s Chair, rock, breathe, and find their peace. Hands always go up. In each of my 19 classes, every day a 3rd, 4th, 5th, or 6th grader quietly walks back to the Peace Place and is welcomed by that space. It is a chance for every student to feel that they have “a seat at the table.” Everyone has a quiet, safe place to simply breathe, rock, and reflect. Many of my special education students find comfort there; students who are having a hard day find solace in Grandma’s rocking chair. The physical act of rocking itself has a therapeutic effect for children and adults. Students use the space not only at the beginning of class, but throughout art class, as needed. It has been an important tool in helping students self-regulate and allows students at Oak Crest to cultivate an authentic relationship of trust with themselves and with their teacher.

An Atmosphere of Peace: As Joyce Bonafield-Pierce wrote, “Peacebuilding is based on an ethic of care.” I want students to understand that I care deeply about them, that I will try my best to treat them with loving kindness, peace, and compassion every day. I began to intentionally verbalize and physically model the word “peace” to explain my classroom environment and climate. In addition to the Peace Place, students enter the Art Room to an atmosphere of soft, calming, instrumental music with nature scenery played on the big screen (“Winter Woods” by Tim Janis is the current selection). Lights are dimmed, but a large bank of windows still brings in plenty of natural light. There is also a small water fountain and battery-operated candles flickering gently up front. We begin class by taking a quiet moment and keeping our bodies so still that the only sound we hear is the trickle of the water. Oftentimes I close my eyes, place a hand on my belly, and just breathe deeply. Once the room feels calm and peaceful, we begin our lesson. I often thank students for taking the moment to be still and quiet their bodies. Students nod, others take a deep breath themselves. Together, we are ready to learn.

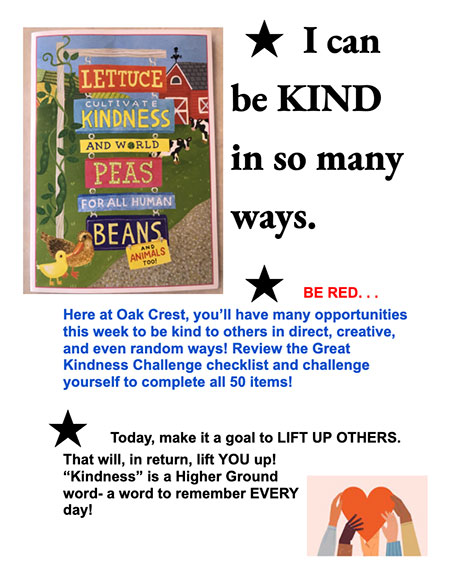

A Lexicon of Peace: To support our Second Step Social/Emotional Curriculum, each Monday during announcements, our principal outlines an important social/emotional skill to focus on for the week, called the “Tiger Target.” To emphasize the Tiger Target, I create an engaging Google doc and type up a kid-friendly explanation of the goal for the week. I let students know that I care enough to take time out of Art Class to help them better understand the importance of these life skills. Often, I reference Joyce Bonafield-Pierce’s Higher Ground words, which appear not only on our Block Party collaborative mural in the hall, but on large chart paper in the classroom.

Developing a lexicon of peace allows me to build relationships with students and teach with a shared vocabulary. Using words that show we respect one another, we step onto Higher Ground and build peace — one word and one action at a time.

I’ve noticed a fundamental shift in how students interact with each other, and how I interact with them. Peacebuilding is happening, slowly but surely. As Ellie Roscher commented, “Lasting work moves slowly, at the speed of trust.” Together, the almost 500 students at Oak Crest Elementary and I are working at the speed of trust, towards cultivating a climate of peace, kindness, and compassion.

Peacebuilding is a deep, profound commitment. To educate for peace, to create a culture of peace in my Art Room that could reverberate throughout our school, I simply started with three elementary blocks important to peacebuilding:

- Create a physical space that supports and upholds teaching for peace

- Set up a calming atmosphere of peace, using the beauty of nature, music and the sound of water, and

- Intentionally model and integrate a shared lexicon of peace

With this work, I truly believe that I am honoring and answering Sachiko’s call: “What is peace? What kind of person should I be? Keep pursuing answers to these questions.” We are genuinely building peace, one building block at a time, in the elementary Art Room.

Envisioning Peacebuilding with Picture Books

Caren: Jacqueline Woodson’s beautiful new picture book The Year We Learned to Fly, illustrated by Rafael Lopez, offers a story of peacebuilding, beginning with the first step— envisioning a new way of living and being. Woodson begins with imagination. On a rainy day, a sister and a brother are stuck inside their apartment, bored and quarreling. Their grandmother steps in and says, “Use those beautiful and brilliant minds of yours. Lift your arms, close your eyes, take a deep breath, and believe in a thing.” Over time, the children lift their arms and learn to fly through their imagination to a better world, a world of justice and freedom that their African and African Americans ancestors believed in, too. When the children move to a new, unwelcoming neighborhood, the children trust in their imaginations to build friendships, spread kindness, and create a neighborhood where everyone can belong — where everyone is welcome at the peacebuilding table. Read aloud The Year We Learned to Fly, and invite children to use their imaginations. What could we do together to turn our homes, schools, and neighborhoods into truly welcoming peace places for all?

Caren: Jacqueline Woodson’s beautiful new picture book The Year We Learned to Fly, illustrated by Rafael Lopez, offers a story of peacebuilding, beginning with the first step— envisioning a new way of living and being. Woodson begins with imagination. On a rainy day, a sister and a brother are stuck inside their apartment, bored and quarreling. Their grandmother steps in and says, “Use those beautiful and brilliant minds of yours. Lift your arms, close your eyes, take a deep breath, and believe in a thing.” Over time, the children lift their arms and learn to fly through their imagination to a better world, a world of justice and freedom that their African and African Americans ancestors believed in, too. When the children move to a new, unwelcoming neighborhood, the children trust in their imaginations to build friendships, spread kindness, and create a neighborhood where everyone can belong — where everyone is welcome at the peacebuilding table. Read aloud The Year We Learned to Fly, and invite children to use their imaginations. What could we do together to turn our homes, schools, and neighborhoods into truly welcoming peace places for all?

Enxpanding the Peacebuilding Team

Ellie: The work of racial reconciliation is one of the most urgent peace building projects of our time. In I Bring the Voices of My People, Dr. Chanequa Walker-Barnes rightfully argues that the voices of black women have long been excluded from the peacebuilding table.

Ellie: The work of racial reconciliation is one of the most urgent peace building projects of our time. In I Bring the Voices of My People, Dr. Chanequa Walker-Barnes rightfully argues that the voices of black women have long been excluded from the peacebuilding table.

Walker-Barnes writes, “The results of this exclusively male gaze are a body of literature and an approach to reconciliation that are less about ending racism than they are about ensuring that White men and men of color have equal access to male privilege” (p 10). The people limited by racism the most, who see it, feel it, and live it every day, are often not leading the peacebuilding efforts, resulting in a world where “much of what passes for racial reconciliation feels like an interracial playdate” (p 203) instead of true, transformational peace building.

An essential step to building peace, regardless of the work’s focus, is to know where we hold systemic power and be acutely aware of who sets the table, who invites folks to the table, who is sitting at the table, and whose voices at the table are given preference and amplified. Authentic relationship is a necessary component here. The lasting work moves slowly, at the speed of trust, which is why peacebuilding is such a revolutionary process in our fast-paced, productivity-driven society. Yet to build strong and transformational peace, the most marginalized voices speaking truth to power must be centered and allowed to imagine and vision the way forward so we may all benefit from reconciliation.

Peacebuilding is the work that will affect our descendants for generations to come. Before the building even begins, how can we set tables that include place settings for folks historically excluded? For children? For our ancestors? How can we join table conversations already in progress? Take a moment to ask—

“What peace are you building?

Who might be missing from the table?”

_________________________

* The term peacebuilding was further described by John Paul Lederach, Director of Eastern Mennonite University’s Conflict Transformation Program and later, Director of the Joan B. Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at Notre Dame University. Among Lederach’s many books are: The Moral Imagination: The Art and Soul of Building Peace, The Little Book of Conflict Transformation, and Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies.

_________________________

For each Peace-ology post, Caren, Ellie, Renee, and Joyce partner to learn and explore the meaning of peace by talking and listening with each other. If you’d like to share your ideas about peace, books, and children, please share your comments here, visit our websites, or connect with Joyce and Renee about their Higher Ground work.