At a meeting at the Dallas Public Library one day, a retired chief executive explained to me his vision for a permanent display on a soon-to-be-renovated floor honoring the men who built up the city’s downtown after World War II.

I looked at him skeptically. “What about the women?”

“There aren’t any,” he snapped back.

Of course there were! But because a group of white men controlled politics in the city for decades, few people know them.

How ironic it was to have this conversation in the Dallas Public Library, which was created only after May Dickson Exall and her women friends raised money for it and convinced Andrew Carnegie to support it. That library, which opened in 1901, housed books on the first floor and a public art gallery on the second, which would later morph into the Dallas Museum of Art.

With every research project, I discover again and again little-known or misrepresented women who made important things happen. This is an old story that’s even more familiar to Native Americans and people of color. But decades after the second women’s movement began, I am still stunned when I encounter it in recent books.

This matters because denying women credit for past accomplishments makes it easier to deny them credit today. And since many readers assume nonfiction books are fact, stereotypes get repeated again and again.

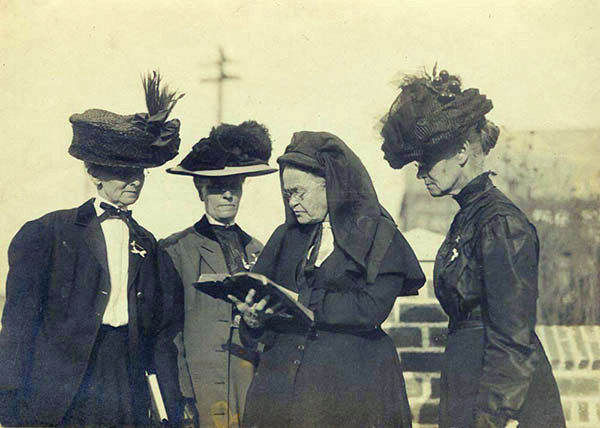

Consider Carry Nation, the woman best know for smashing up saloons in the turn-of-the-century run-up to prohibition. Newsmen at the time ridiculed her, questioned her sanity, and portrayed her as some kind of oversized freak.

So did more recent authors. She “was six feet tall, with the biceps of a stevedore, the face of a prison warden, and the persistence of a toothache,” wrote author Daniel Okrent in Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (2010), the book that was the basis of Ken Burns’ prohibition documentary.

Edward Behr, author of Prohibition: Thirteen Years that Changed America (1996), wrote that she was “so unbalanced and out of control” that she “might well have been confined to a mental institution.”

In reality, photos (and other writers) show Nation couldn’t possibly have been six-feet tall, although Britannica.com and the State Historical Society of Missouri also say so. Though her actions were radical, I concluded in my book Bootleg: Murder, Moonshine, and the Lawless Years of Prohibition that they grew out of personal experience with an alcoholic first husband, ministering to people in jail with drinking problems, and a deep religious conviction. She was angry, no doubt. But a thoughtful biography by Fran Grace, Carry A. Nation: Retelling the Life (2004), portrays her as committed, not crazy.

In reality, photos (and other writers) show Nation couldn’t possibly have been six-feet tall, although Britannica.com and the State Historical Society of Missouri also say so. Though her actions were radical, I concluded in my book Bootleg: Murder, Moonshine, and the Lawless Years of Prohibition that they grew out of personal experience with an alcoholic first husband, ministering to people in jail with drinking problems, and a deep religious conviction. She was angry, no doubt. But a thoughtful biography by Fran Grace, Carry A. Nation: Retelling the Life (2004), portrays her as committed, not crazy.

As Nation famously said, “You wouldn’t give me the vote, so I had to use a rock!”

More recently, I’ve been steeped in Bonnie and Clyde lore for a nonfiction book out in August. Bonnie Parker is a complicated character and every writer struggles to define her: Was she the leader, a follower or a co-conspirator?

But there’s another temptation for male writers, familiar to every female who ever went to high school. That’s to call her a slut or even a prostitute.

The implication that she may have engaged in prostitution likely started with detective magazines of the 1930s, which embellished stories much like supermarket tabloids today. Some contemporary authors allude to it, but in Texas Ranger: The Epic Life of Frank Hamer, The Man Who Killed Bonnie and Clyde (2016), author John Boessenecker simply states she worked as a part-time prostitute before she met Clyde, and that Dallas police “knew Bonnie as a street-walker but never arrested her.”

His source? A 1991 local history column in the Seguin, Texas, newspaper written by a barber, who attributed the information to unnamed “old Dallas policemen.” Since Bonnie and Clyde had been dead 57 years by then, those policemen must have been very old.

To be sure, Bonnie was a married woman living on the road with a man who was not her husband. But there is no evidence that Bonnie ever worked as a prostitute.

A lot, of course, has changed. More and more children’s books are highlighting ground-breaking women. Just a few days ago, the New York Times printed a special section of women whose obituaries were previously overlooked, with a promise to keep adding names. I know for a fact that the Dallas Library director will never have an all-male display in her building.

But stereotypes persist. Here are a few things that writers, educators, and librarians might do to give women their due:

Consider the source. I love primary sources, including documents and contemporary newspapers and magazines. But they have to be put in the context of their times. Women were legally considered their husbands’ property for hundreds of years. They couldn’t borrow money or own land. They were denied entrance to law schools, medical schools, and graduate schools because of their gender. Many of these laws didn’t change until the 1970s. Don’t assume today’s standards when reading or writing about women from a different era.

Question, Question, Question! Were girls really weak? Did women really faint? Would her temper or impatience have mattered if she were a man? Is her hair, attractiveness, or body shape relevant? Do female writers tell a different story?

Include women in every unit of study. In almost every topic area these days — the Civil War, both World Wars, science, the environment, math, technology, politics, art, music and so on — there are good kids’ books about what women contributed. Share them.

Do your own research. Consider a class project to identify and research a lesser-known woman or person of color who made a difference in your community. While highways and big buildings are usually named after men, there’s probably a name on a local park, school, or nearby street to get you started. Your local library or historical or genealogical society would probably be thrilled to help.

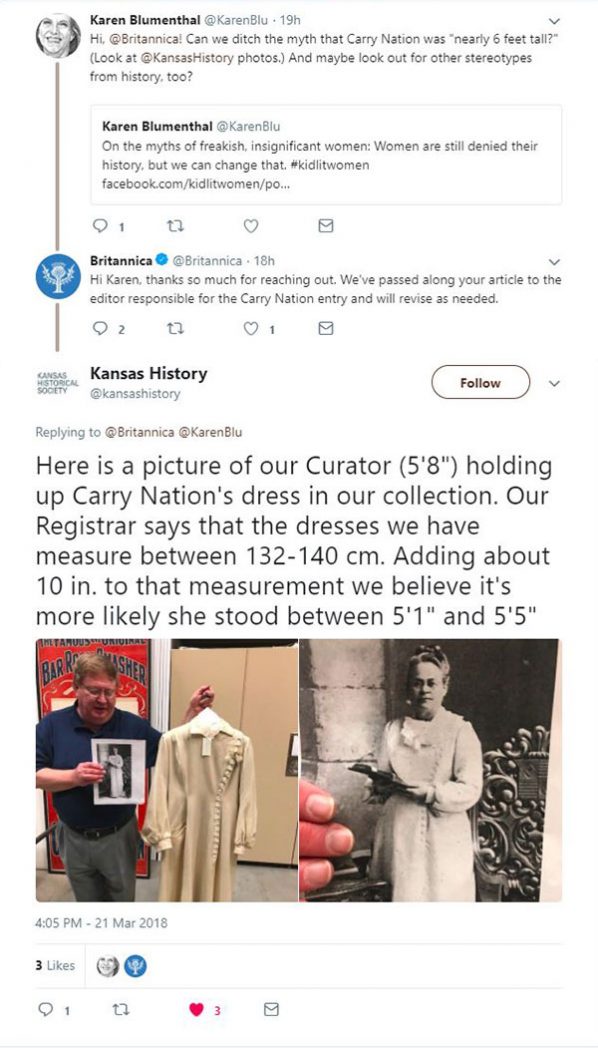

[Ed: As this article circulated, Karen Blumenthal tweeted the Britannica encyclopedia folks about the discrepancy in fact concerning Carrie Nation’s height. Here’s what happened. You and your students can have a positive effect on factual information.]

I’ve been working with the Wikipedia ‘Women in Red’ project, for which we are adding these missing women to Wikipedia (a name in red means there is no page for it). It’s an important exercise as only a very small percentage of the biographies on Wikipedia are about women. The reason? Finding printed references to these women is difficult as they truly were written out of history. But, we will persist!